Urinary retention is a condition where the bladder does not empty properly.

For many people, it starts as a heavy or tight feeling in the lower abdomen. You may feel a strong urge to urinate but struggle to start, strain to pass urine, or release only a small amount even though your bladder still feels full.

This can be uncomfortable, frustrating, and sometimes painful.

In some cases, urinary retention happens suddenly and causes severe pain and pressure. In others, it develops slowly over time.

Because these symptoms can build up gradually, they are sometimes ignored until the discomfort becomes hard to manage.

Urinary retention can affect both men and women and may be linked to blockages, nerve problems, medications, infections, or recent surgery.

This guide explains what urinary retention is, its causes, signs, and symptoms, how it is diagnosed, and the treatment options available, so you can better understand what is happening and what steps to take next.

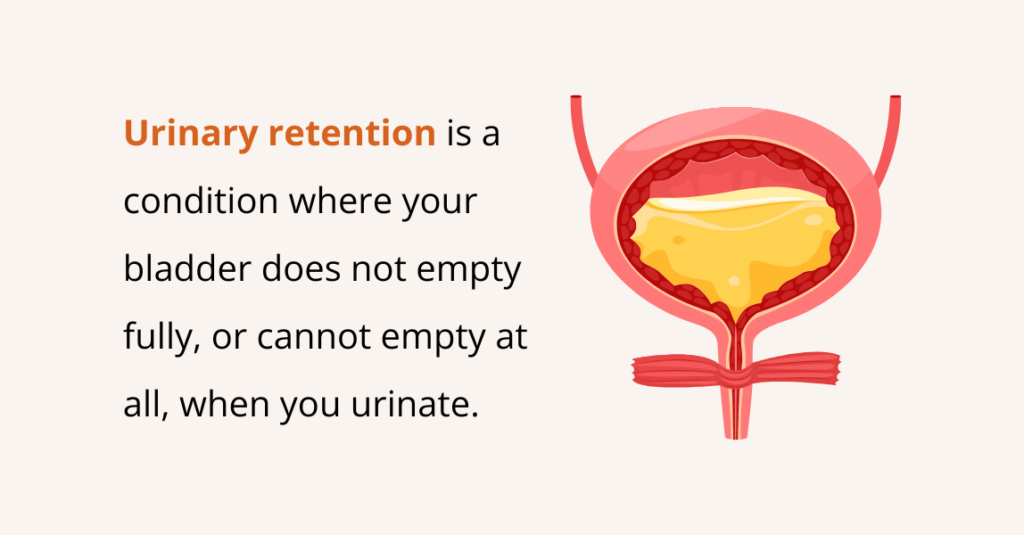

What is Urinary Retention?

Urinary retention is a condition where your bladder does not empty fully, or cannot empty at all, when you urinate (pee). This means urine stays trapped inside the bladder instead of flowing out normally.

Your bladder works like a storage tank. Your kidneys filter waste from your blood and turn it into urine. That urine travels to your bladder, where it is stored until you’re ready to urinate.

When you pee, the bladder muscles squeeze, and urine flows out through the urethra.

With urinary retention, this process does not work properly. The bladder may not squeeze properly, the urethra may be blocked, or the nerves may not send the right signals. As a result, urine stays in the bladder, causing pressure, discomfort, and other urinary problems.

What Causes Urinary Retention?

Urinary retention can happen for several different reasons. Common causes can include:

- A blockage in the urine flow

- Medications that affect the nervous system

- Nerve problems that stop the brain and the urinary system from communicating

- Infections or inflammations can block or slow the flow

- Surgery or anesthesia can cause retention

While these causes apply to both men and women, the specific reasons for urinary retention often differ by sex due to anatomical differences and common health conditions.

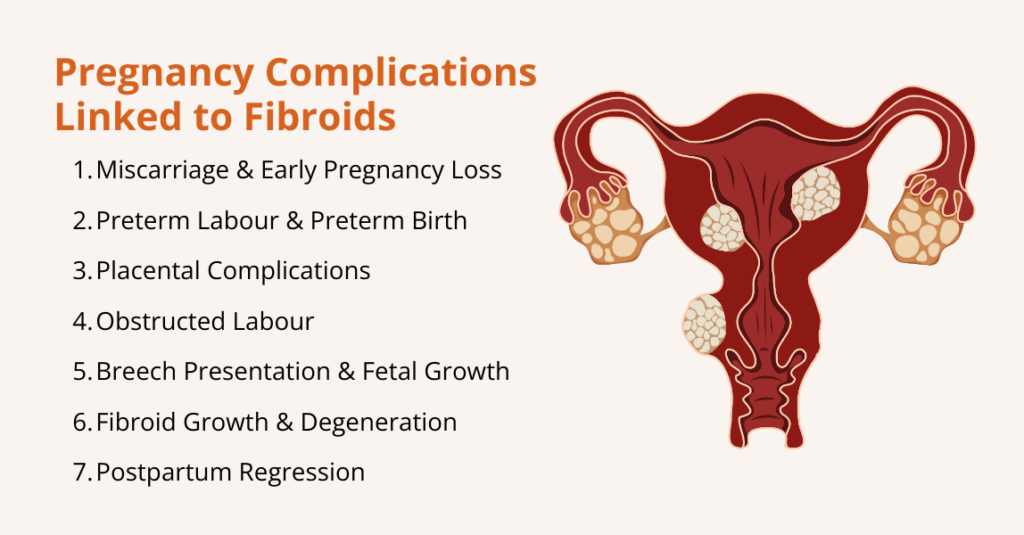

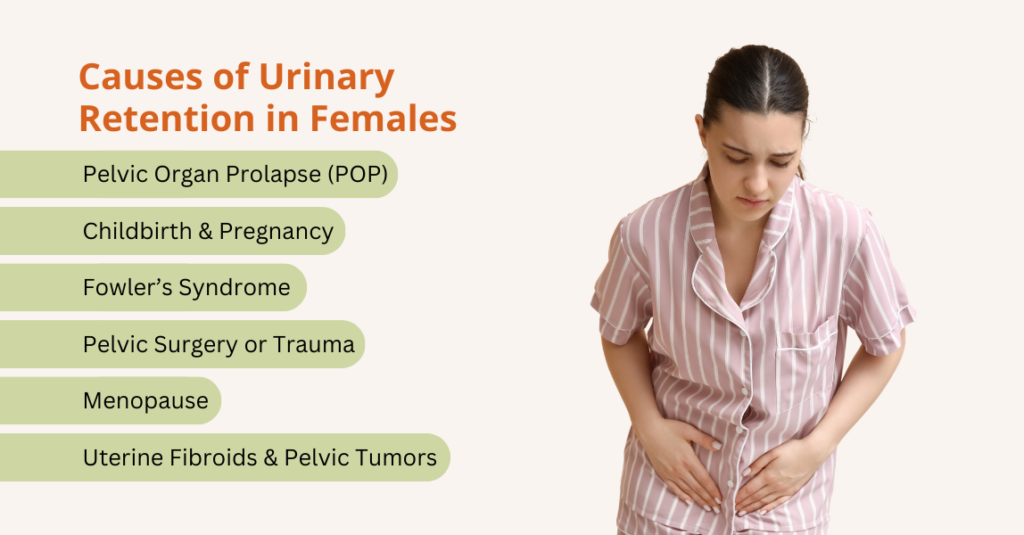

What are the Causes of Urinary Retention in Females?

The most common and female-specific causes include:

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP)

Sometimes the bladder, uterus, or other pelvic organs sag or drop down. When the bladder bulges into the vagina (a cystocele), it can kink the bladder outlet or press on the urethra, making it hard to empty fully.

Childbirth & Pregnancy

Pregnancy and vaginal delivery can stretch or injure the pelvic muscles and nerves that help you pee. A very full uterus or an unusual uterus position (like a retroverted uterus) can press on the bladder.

Epidural anesthesia during labor can also make the bladder less able to squeeze for a short time.

Fowler’s Syndrome

A less common problem in younger women is where the ring of muscle around the urethra (the sphincter) doesn’t relax properly. That tightness obstructs urine flow even when the bladder is full.

Pelvic Surgery or Trauma

Operations on the pelvis (for example, for urine incontinence or hysterectomy) or injuries can damage nerves or change the shape of pelvic organs. That can weaken bladder control or cause a physical condition that impedes the flow of urine.

Menopause

Lower hormone levels after menopause result in thinner, less elastic pelvic tissues. The urethral opening can narrow, and weak tissues can alter the position of the bladder and urethra, which may lead to difficulty emptying.

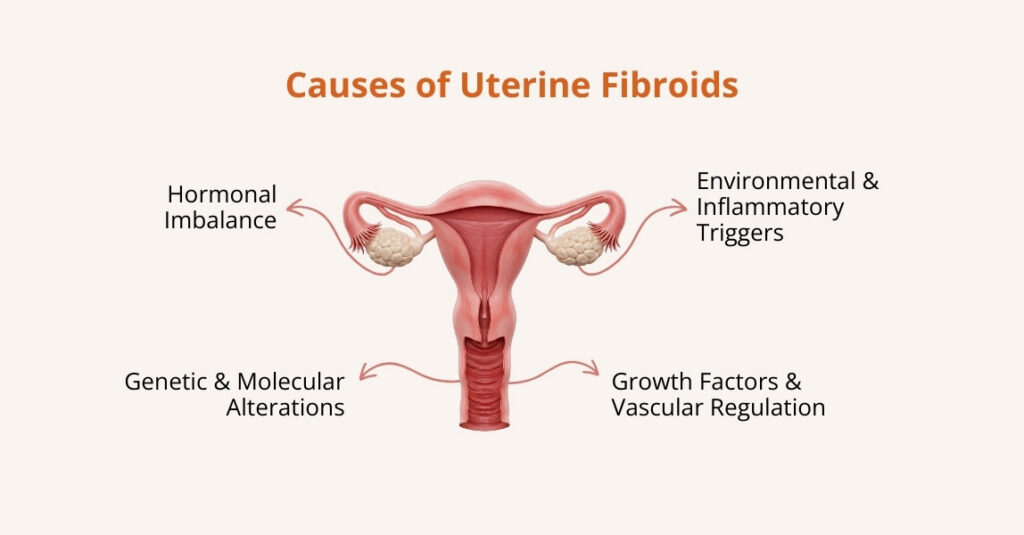

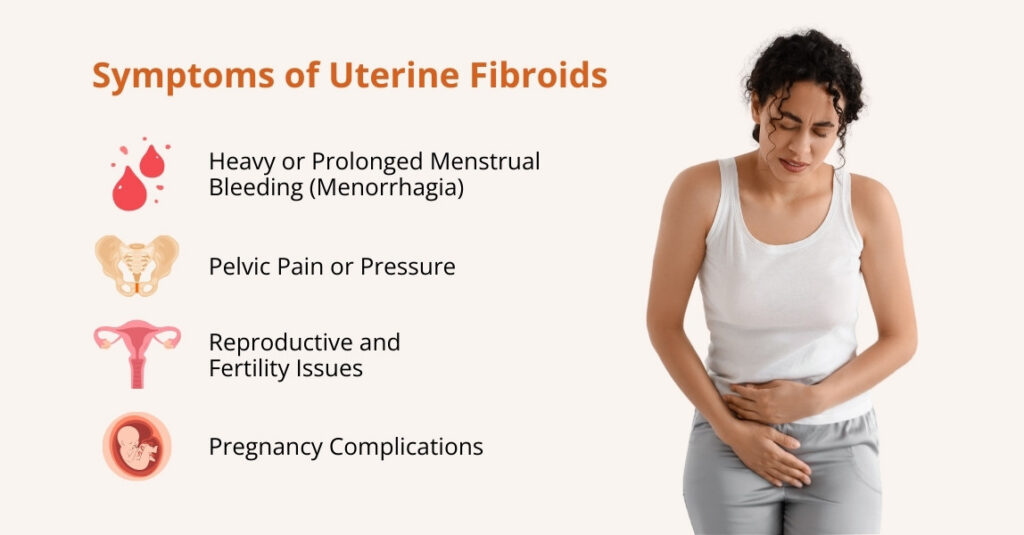

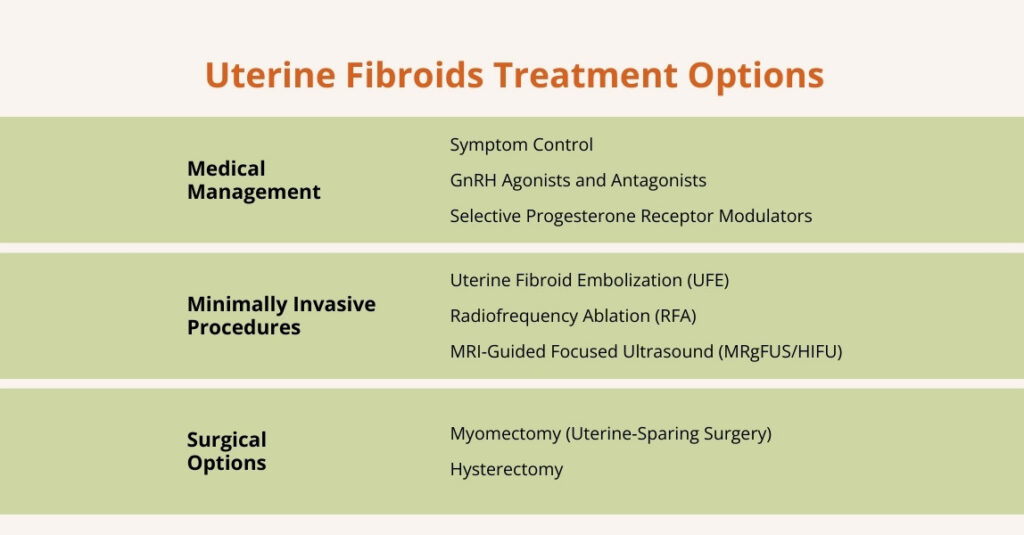

Uterine Fibroids and Pelvic Tumors

Noncancerous growths (fibroids) or other pelvic masses can press on the bladder or urethra. That pressure can partially obstruct urine flow or make it difficult to fully empty the bladder.

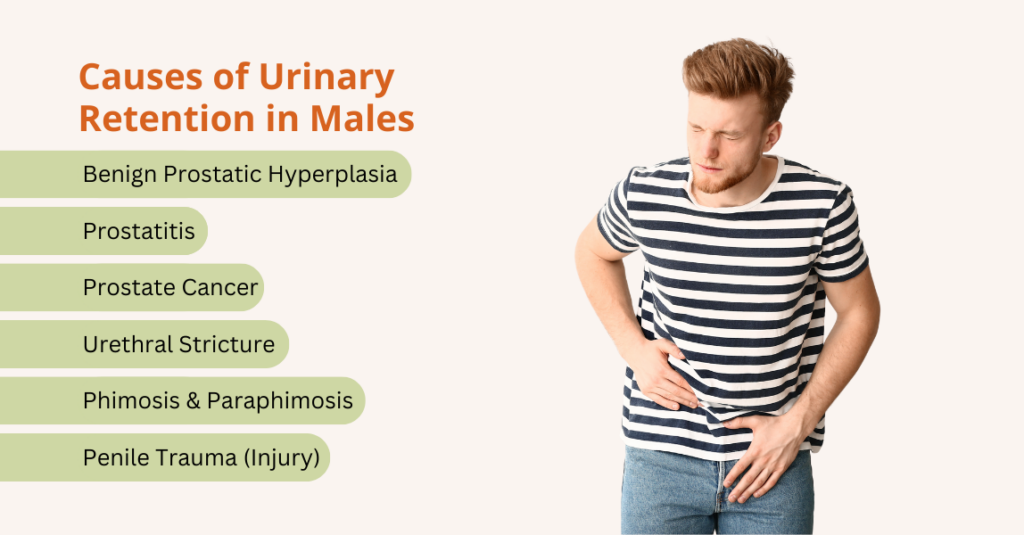

What are the Causes of Urinary Retention in Males?

The most common and male-specific causes include:

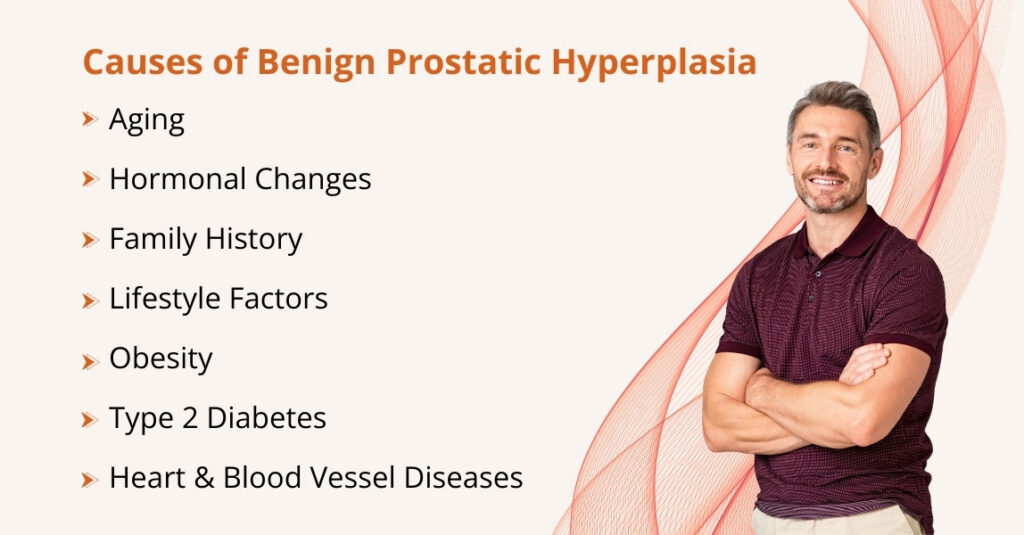

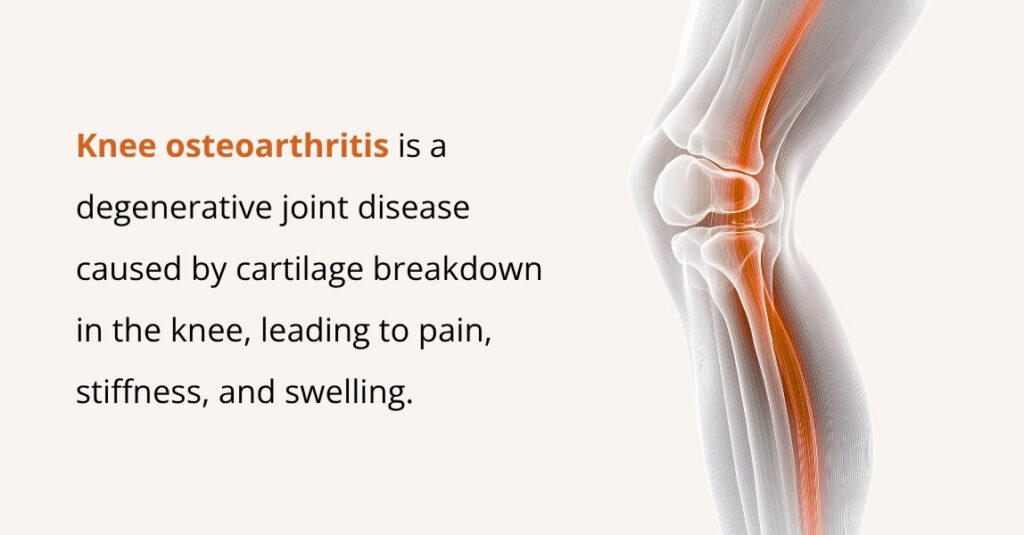

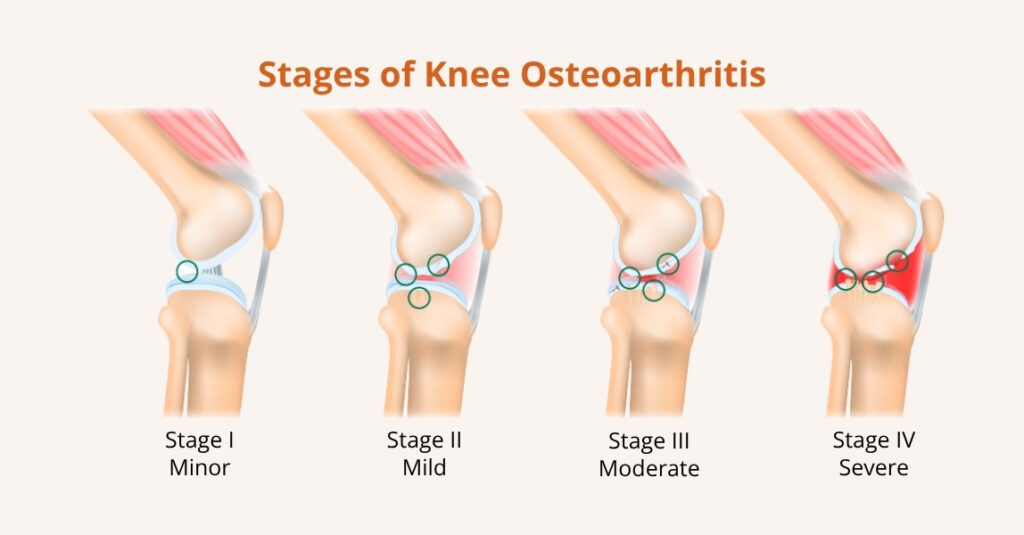

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

As men get older, the prostate gland often becomes enlarged. The prostate sits just below the bladder and surrounds the urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the body). When it enlarges, it can squeeze the urethra, slowing or blocking urine flow.

Prostatitis

Prostatitis is inflammation or infection of the prostate. It can cause the prostate to swell suddenly, narrowing the urethra.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer can also press on the urethra and block urine flow. Unlike infections, this usually develops slowly over time.

Urethral Stricture

A urethral stricture occurs when scar tissue narrows the urethra. This scar tissue can form after injury, surgery, catheterization, or infection (e.g., sexually transmitted infections), restricting urinary flow.

Phimosis and Paraphimosis

These conditions affect uncircumcised men.

- Phimosis happens when the foreskin cannot be pulled back over the tip of the penis, which can trap urine and cause swelling.

- Paraphimosis occurs when the foreskin is pulled back but cannot return to its normal position, causing painful swelling that can block urine flow.

Penile Trauma (Injury)

Injury to the penis, such as from an accident, fall, or sports injury, can cause swelling, bleeding, or damage to the urethra. This swelling or damage can block urine flow and lead to sudden urinary retention.

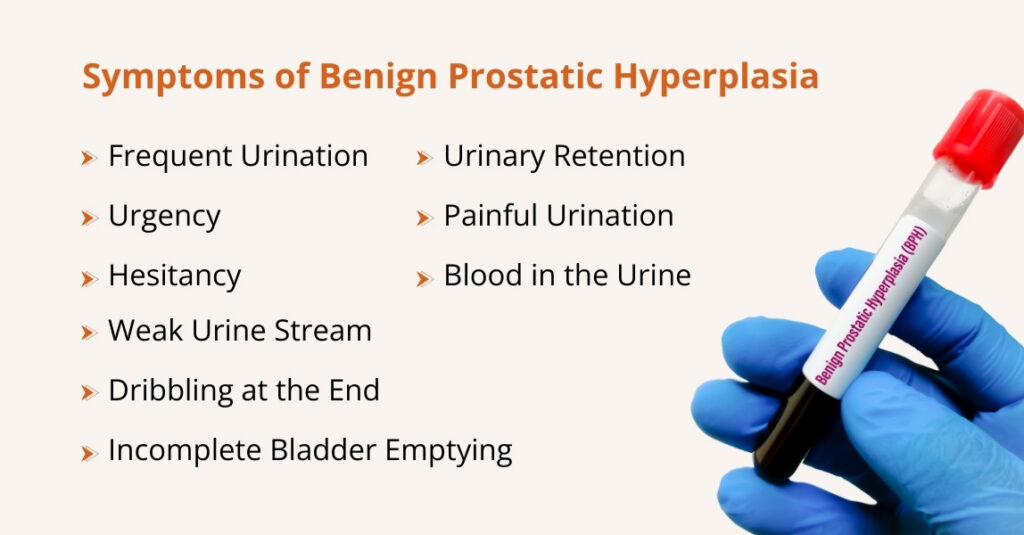

What are the Signs and Symptoms of Urinary Retention?

The symptoms of urinary retention can be different depending on whether it is acute (sudden) or chronic (long-term).

Some people, especially those with nerve damage, may not feel pain even when the bladder is not emptying properly.

Acute (Sudden)

People with acute urinary retention (AUR) may experience:

- Sudden inability to urinate despite a strong urge

- Severe pressure, pain, or discomfort in the lower abdomen

- Swelling or bloating in the lower belly

- Lower back pain

Chronic (Long-Term)

Chronic urinary retention (CUR) typically develops gradually and may not cause severe pain initially. People with chronic urinary retention may experience:

- Trouble starting urine flow

- A weak or slow urine stream

- A urine stream that stops and starts

- A strong urge to urinate, but passing only a small amount

- Feeling the need to urinate again right after going

- Frequent trips to the bathroom, including at night

- Mild, ongoing discomfort in the lower abdomen or urinary tract

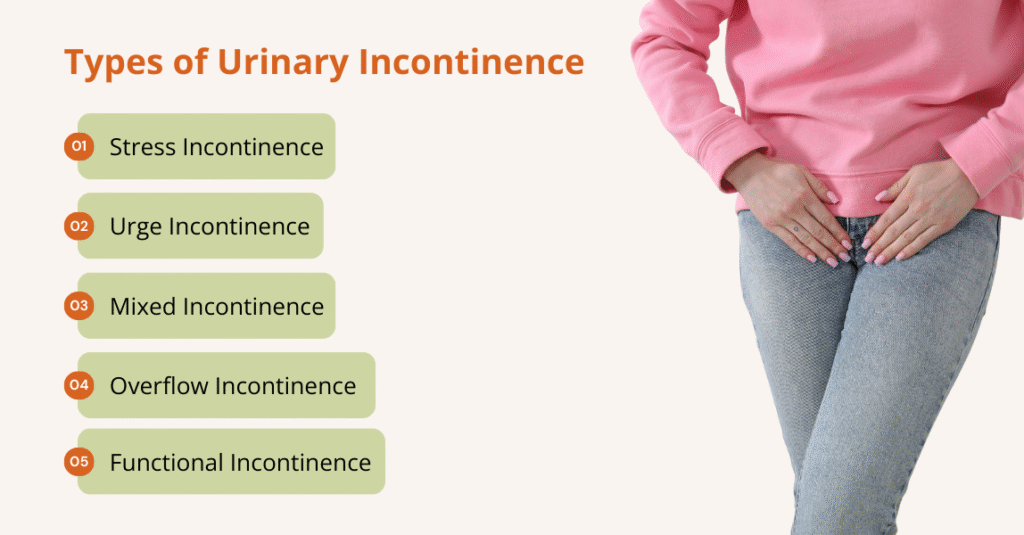

- Leakage of urine during sleep or at rest due to bladder overflow

How is Urinary Retention Diagnosed?

Healthcare professionals diagnose urinary retention by reviewing your medical history, performing a physical exam, and measuring how much urine remains in your bladder after you urinate (called a post-void residual).

Additional lab tests and imaging studies may be ordered to find the exact cause.

Medical History

Your health care professional will ask detailed questions about your health and symptoms, including:

- Urinary symptoms (also called lower urinary tract symptoms)

- Current and past medical conditions, surgeries, or catheter use

- Prostate problems (in men)

- Pregnancy and childbirth history (in women)

- Over-the-counter and prescription medications

- Eating and drinking habits

- Bowel habits

This information helps identify possible triggers or underlying causes.

Physical Exam

A physical exam is done to look for signs of bladder or nerve problems. This may include:

- Checking your lower abdomen for a full or swollen bladder

- A rectal exam to examine the prostate (in men)

- A pelvic exam (in women)

- A basic neurological exam to assess nerve function

Post-Void Residual (PVR) Urine Measurement

A post-void residual test measures how much urine remains in your bladder after you urinate. The leftover urine is called the post-void residual.

This test is done using:

- A small catheter is placed briefly into the bladder, or

- A bladder ultrasound scan

- A high amount of leftover urine suggests urinary retention.

Lab Tests

Your health care professional may order lab tests to look for conditions linked to urinary retention, such as:

- Urinalysis: Checks for urinary tract infection (UTI), kidney problems, or diabetes

- Blood tests: Check kidney function and chemical imbalances in the body

You may be asked to provide a urine sample for testing.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests help identify structural problems or blockages in the urinary tract. These may include:

- Ultrasound: Uses sound waves to view the bladder, kidneys, and urinary tract

- Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG): Uses X-rays to show how urine flows through the bladder and urethra

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): Creates detailed images of the urinary tract and spine

- CT scan: Provides detailed cross-sectional images of the urinary system

Urodynamic Testing

Urodynamic tests check how well the bladder, urethra, and sphincter muscles store and release urine. These tests may include:

- Uroflowmetry: Measures how much urine you pass and how fast

- Pressure-flow studies: Measure bladder pressure and urine flow during urination

- Video urodynamics: Uses images or video to show bladder filling and emptying

- Cystometry: Measures bladder capacity and pressure as it fills

- Electromyography: Tests how well nerves and muscles around the bladder work together

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is a procedure in which a thin, flexible tube with a camera (a cystoscope) is inserted into the urethra to visualize the urethra and bladder. This helps doctors check for:

- Blockages or narrowing

- Inflammation or infection

- Tumors or cancer

- Structural abnormalities

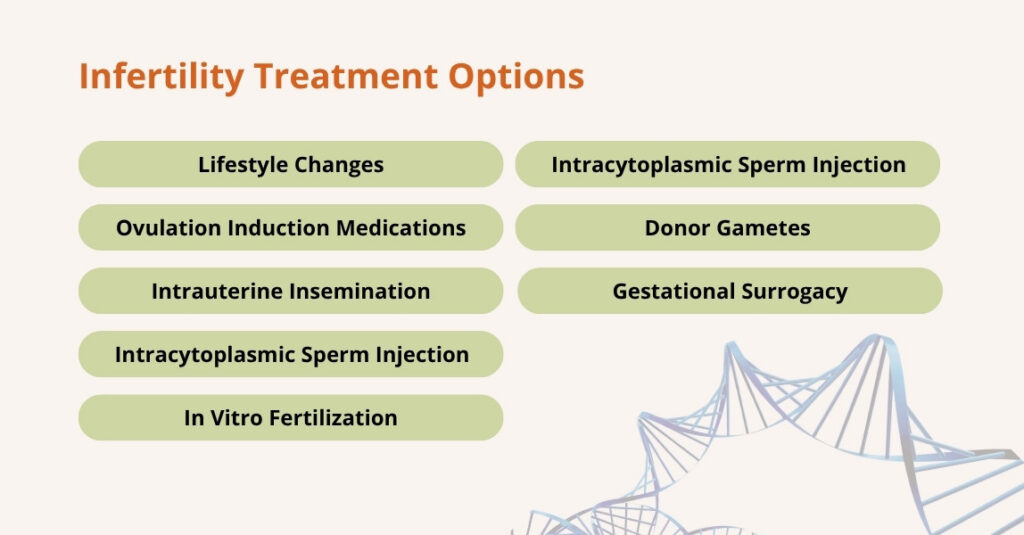

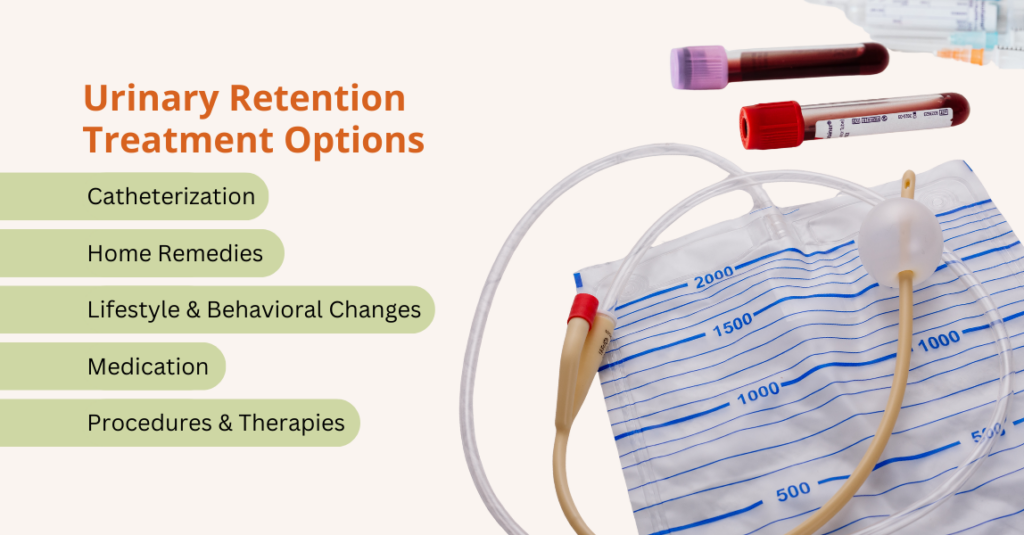

Urinary Retention Treatment Options

There are several treatment options for urinary retention, including the following:

Catheterization

Acute urinary retention is a medical emergency. If you suddenly can’t pee at all, a doctor will quickly drain your bladder. This is usually performed by inserting a thin tube (a catheter) through the urethra into the bladder to allow urine to flow out.

Draining the bladder relieves pain and prevents damage to your bladder or kidneys. Once the bladder is empty, doctors will treat the cause (for example, an enlarged prostate, a blood clot, or an infection).

In some cases of long-term (chronic) retention, people learn to use a catheter at home to empty their bladder regularly.

Home Remedies

While medical treatment is essential for urinary retention, some gentle at-home tricks can help encourage urination. These are not cures, but they may make it easier to go until you can see a doctor:

- Warm water and sound: Sit on the toilet and run warm water from the tap. The sound and feel of warm water can sometimes trigger bladder emptying.

- Warm bath or perineal rinse: A warm sitz bath or rinsing the genital area with warm water can relax pelvic muscles.

- Body position and relaxation: Lean slightly forward while sitting on the toilet (for women, putting feet on a small stool) and take deep breaths.

- Walking and gentle movement: Sometimes a short walk or light activity can help stimulate bladder function or relieve constipation, which in turn can facilitate urination.

- Peppermint oil: Some individuals report that the scent of peppermint oil may facilitate urination.

- Herbal teas: Teas made from herbs such as dandelion or stinging nettle are sometimes used to relieve bladder symptoms.

If you still cannot urinate or have severe pain, seek medical help right away. Home tips are intended only for mild cases or for use while waiting for care.

Lifestyle & Behavioral Changes

Certain habits and exercises can support treatment and ease symptoms over time. These changes are especially useful for chronic retention or after initial treatment:

- Bladder training: Go to the toilet at regular times, even if you don’t feel a strong urge. For example, try urinating every 2–4 hours.

- Double voiding: After you urinate, wait a minute and then try again. This “double peeing” helps make sure your bladder is as empty as possible.

- Relax on the toilet: Take a moment to relax while seated fully. Breathe deeply and give yourself time. For women, sitting with the knees apart (or even slightly squatting) allows the pelvic muscles to relax more effectively.

- Fluid management: Drink adequate water during the day, but limit fluids before bedtime to avoid nocturnal retention.

- Avoid bladder irritants: Cut down on caffeine (coffee, tea, cola), alcohol, and carbonated drinks, as these can irritate the bladder and make retention worse.

- Go when you need to: Don’t “hold it” when you feel the urge. Responding promptly to the urge to urinate helps prevent bladder overstretching.

- Manage constipation: Straining during defecation can worsen retention by compressing the bladder or pelvic nerves.

- Weight and posture: Maintaining a healthy weight and good posture can reduce pressure on pelvic organs. Lifting properly (bending the knees, not the back) can also help prevent problems.

Making these changes takes time, but they are low-risk ways to help your bladder. Always discuss lifestyle plans with your doctor or nurse.

Medication

Your health care provider may prescribe medicines to treat the underlying cause of urinary retention. The type of medication depends on what is preventing your bladder from emptying properly.

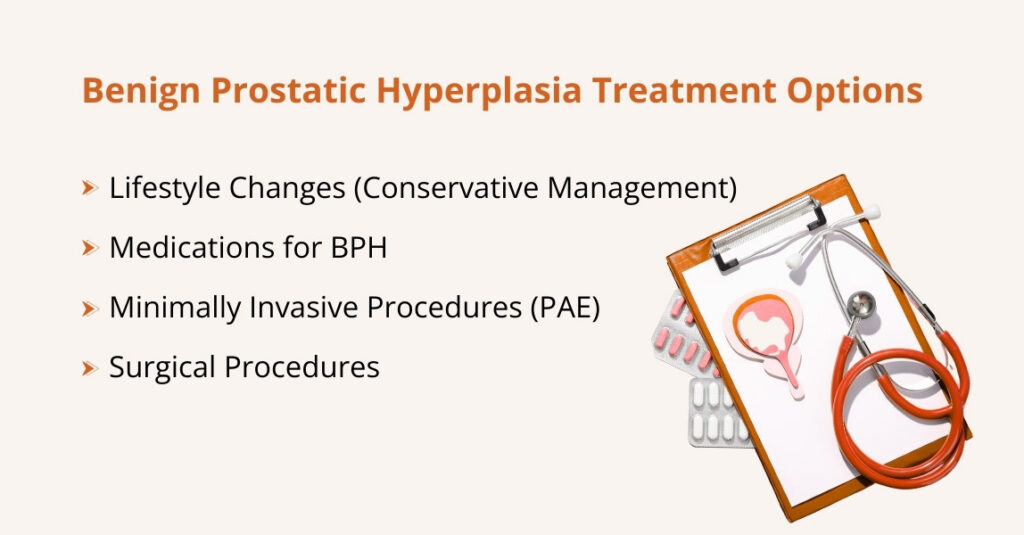

- Enlarged prostate (in men): Medicines such as alpha-blockers help relax the muscles around the prostate and bladder neck, making it easier for urine to flow. 5-alpha reductase inhibitors work by slowly shrinking the prostate, which can reduce blockage over time.

- Infections: If an infection is causing swelling or blockage, antibiotics are used to clear the infection and relieve urinary retention.

Medical Procedures

If medicines and behavior changes aren’t enough, doctors have many procedures and therapies to fix the cause of retention:

- Cystoscopy and stone removal: A cystoscope is a thin, lighted tube passed into the bladder. It allows the physician to see inside and remove any stones or growths obstructing urine flow.

- Prostate artery embolization (PAE): PAE is a minimally invasive, image-guided procedure used to treat symptoms of an enlarged prostate caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). During the procedure, blood flow to the prostate is reduced, causing it to shrink and relieving pressure on the urethra.

- Urethral dilation: If a urethral stricture (scar tissue narrowing the urethra) is the problem, the doctor can stretch or widen the urethra during an office visit.

- Vaginal pessary (women): In women with pelvic organ prolapse, a pessary is a removable ring placed inside the vagina to hold the bladder up.

- Pelvic floor therapy: A specialized pelvic-floor therapist can use biofeedback, electrical stimulation, or manual techniques to improve pelvic muscle function.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can UTI cause urinary retention?

Yes, a urinary tract infection (UTI) can cause urinary retention. When the bladder or urethra becomes inflamed or swollen due to infection, it can block or slow the flow of urine. In some cases, the bladder muscles may also become weak or unable to contract properly, making it difficult to empty the bladder completely. Urinary retention and UTIs can also make each other worse: urine left in the bladder provides a place for bacterial growth, increasing the risk of infection. If you experience difficulty urinating along with symptoms of a UTI, such as burning, urgency, or lower abdominal discomfort, it’s essential to seek medical care promptly.

Can urinary retention be cured?

Yes, urinary retention can often be cured or well-managed. Treatment usually involves draining the bladder and addressing the underlying cause, which may include an enlarged prostate, infections, or nerve problems. Depending on the cause, doctors may use catheters, medications, pelvic floor therapy, or surgery to restore normal urination, relieve discomfort, and improve bladder function.

Does constipation cause urinary retention?

Yes, constipation can contribute to urinary retention. A full rectum can press on the bladder or urethra, making it hard to empty, and straining can weaken pelvic muscles or interfere with the nerves that control urination. This can lead to incomplete bladder emptying and increase the risk of urinary tract infections.

Can you die from urinary retention?

Yes, urinary retention can be life-threatening, but usually only if complications develop. When urine stays in the bladder for too long, it can lead to serious infections that may spread to the kidneys or bloodstream, causing sepsis, a dangerous body-wide reaction that can result in organ failure. It can also cause acute kidney damage if the blockage prevents urine from leaving the body.

What can urinary retention lead to?

Urinary retention can lead to several complications if it isn’t treated, including:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs): Residual urine allows bacteria to grow, increasing the risk of recurrent or severe infections.

- Bladder damage: A chronically overfilled bladder can stretch and weaken, reducing its ability to contract and empty.

- Overflow incontinence: The bladder may leak small amounts of urine when it becomes overly full.

- Urine backup in the kidneys (hydronephrosis): A blockage can cause urine to flow backward into the kidneys, leading to swelling and damage.

- Acute kidney injury/chronic kidney disease: Severe or prolonged obstruction can impair kidney function.

- Sepsis (blood infection): A UTI that spreads can lead to life-threatening sepsis, particularly in older adults or immunocompromised individuals.

- Stones and irritation: Stagnant urine can lead to bladder stones and ongoing irritation or inflammation.

- Sexual dysfunction & reduced quality of life: Ongoing urinary problems can affect sexual function, sleep, mood, and daily activities.

- Falls or injuries: Nighttime urgency or hurried bathroom trips increase the risk of falls, particularly among older adults.

- When to get urgent care: inability to urinate at all, severe belly pain, fever, chills, confusion, vomiting, fainting, or decreased urine output. These can signal serious complications and need immediate medical attention.

How long before urinary retention is dangerous?

If urinary retention is acute (sudden), it becomes dangerous right away, and you should seek emergency care the moment you cannot urinate because immediate bladder drainage is needed to prevent pain and complications. Research shows that obstruction can cause acute kidney injury within hours to days, and the risk of lasting kidney damage rises noticeably after about 48–72 hours of ongoing blockage. Whereas chronic (long-term) retention is less often immediately life-threatening but can slowly cause bladder damage, infections, stones, and kidney problems over weeks to months if not treated.

How long does post-operative urinary retention last?

Postoperative urinary retention (POUR) usually improves on its own, with most patients regaining normal urination within a few days to a few weeks after surgery. In some cases, it can last 4–6 weeks, and rarely even longer, depending on the type of surgery, anesthesia used, and individual factors. Retention often resolves as the effects of anesthesia wear off and urinary tract swelling decreases. Still, prolonged cases may require additional interventions, such as catheterization, medications, or further evaluation by a healthcare provider.

How to prevent urinary retention?

You can often reduce the risk of urinary retention by addressing factors that compress the bladder, interfere with emptying, or disrupt nerve function. Here’s how:

- Perform pelvic floor exercises (Kegels) or consult a pelvic floor therapist to maintain muscle function.

- Avoid constipation by increasing fiber intake, maintaining adequate hydration, exercising, and using gentle laxatives or stool softeners if needed, as a full rectum can press on the bladder.

- Drink regularly during the day but cut down before bedtime; avoid excess caffeine and alcohol that irritate the bladder.

- Get UTIs or prostatitis checked and treated promptly so swelling does not block urine flow.

- Review medicines with your clinician, as some drugs (antihistamines, strong painkillers, decongestants) can cause retention; your doctor may adjust them.

- Manage prostate and pelvic conditions, follow up for BPH, prolapse, or fibroids, so mechanical blockages are identified and treated.

- Sit properly, take your time, try “double voiding” (pee, wait a minute, try again), and don’t ignore urges.

- After surgery, follow post-op care, as early walking, pain control, and close bladder checks reduce the risk of postoperative retention.

- See your doctor for regular checks if you have diabetes, spinal problems, prior pelvic surgery, or recurrent urinary issues.

If you start having trouble emptying your bladder, sudden inability to urinate, severe pain, fever, or worsening symptoms, seek medical help right away.

Doctors who treat acute urinary retention

Doctors who treat acute urinary retention (AUR) are mainly urologists, specialists in the urinary and reproductive systems, who manage immediate bladder drainage with a catheter and treat the underlying cause through medications or procedures. If you cannot see a urologist immediately, going to the emergency room is essential, where an emergency physician can provide urgent care and relieve the obstruction. Other healthcare professionals, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pelvic floor physical therapists, may also be involved in ongoing management and rehabilitation to prevent recurrence and improve bladder function.

Conclusion

Urinary retention can be uncomfortable, frustrating, and even frightening, especially when you feel a full bladder but cannot urinate.

This condition is fairly common and can occur suddenly (acute) or develop over time (chronic), with causes ranging from infections, an enlarged prostate, nerve problems, pelvic organ prolapse, to certain medications.

As a result, symptoms can vary widely, from difficulty starting urination and a weak urine stream to an inability to urinate, lower abdominal pain, or frequent urination.

To determine the cause, diagnosis typically involves obtaining a detailed medical history, performing a physical examination, performing urinalysis, and, in some cases, using imaging or specialized bladder studies.

Based on the findings, treatment depends on the severity and underlying cause of the retention. Available options include immediate catheterization, medications, nonsurgical therapies, lifestyle adjustments, and, when necessary, surgical intervention.

It is important to remember that if you are experiencing urinary difficulties, you are not alone, and medical help is available to restore comfort, improve bladder function, and provide peace of mind.