Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a common and growing public health concern in the United States.

As people live longer and rates of obesity rise, more Americans are developing this degenerative joint disease, leading to major personal and societal costs.

In fact, research estimates that about 14 million U.S. adults suffer from symptomatic knee OA.

Moreover, radiographic studies from the U.S. show that more than one in three adults aged 60 or older have signs of knee OA on imaging, and around 12 percent report symptoms.

As the population ages and obesity continues to climb, resulting in knee OA prevalence rising further, understanding risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment is more important than ever.

In this article, we’ll walk through what knee osteoarthritis is, how it progresses, who’s most at risk, what causes it, how it’s diagnosed, treatment options, and finally, strategies for prevention.

What is Knee Osteoarthritis?

Knee osteoarthritis occurs when the cartilage that cushions your knee joint gradually wears down. As this protective layer thins, the bones begin to rub against each other, creating friction that leads to pain, swelling, and stiffness.

Because the knee carries your body weight and absorbs impact with every step, it’s one of the joints most commonly affected by this degenerative “wear-and-tear” disease.

Research shows that OA of the knee joint is often associated with aging, but it can also be influenced by factors such as injury, obesity, genetics, and other health conditions.

As the condition worsens, individuals may experience difficulty performing daily activities, such as walking, climbing stairs, or getting up from a chair. Over time, though, the disease can worsen and may eventually limit mobility.

However, many treatments can help slow its progression, reduce pain, and improve everyday function. Healthcare providers carefully monitor its progression, and if knee OA begins to significantly affect your quality of life, surgical and non-surgical options are available.

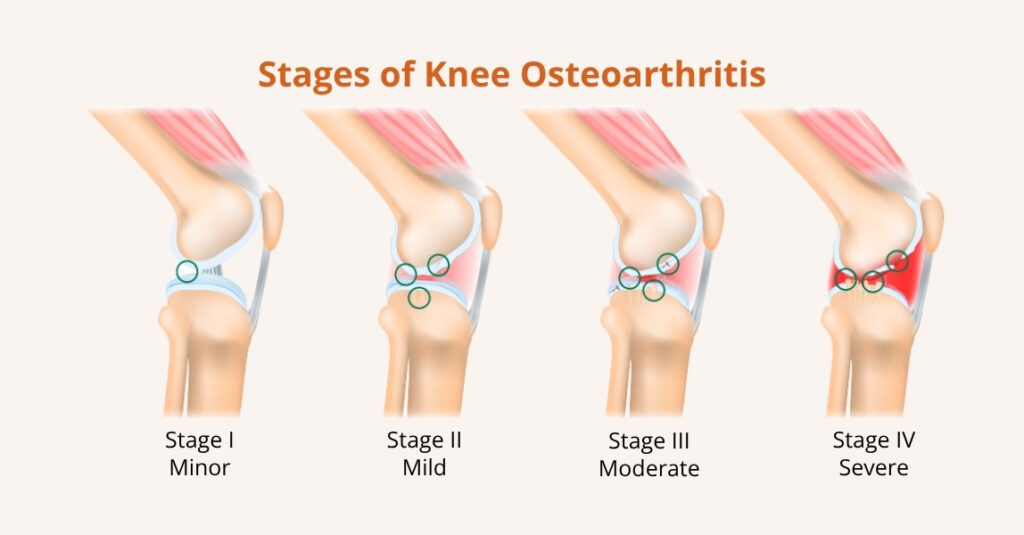

What are the Stages of Knee Osteoarthritis?

Although there’s no single universal staging system, knee osteoarthritis typically follows a predictable, gradual course.

Clinicians often describe it in stages to explain how advanced the disease is and what to expect.

Knowing these stages can help you recognize symptoms early and plan treatment with your healthcare team.

- Stage 1 (Minor)

At this earliest stage, there is minor wear and tear to the cartilage. Changes are usually subtle, and most people feel little or no pain. X-rays may show only very subtle changes, if any at all.

- Stage 2 (Mild)

Mild OA means the cartilage is beginning to break down. You may notice occasional pain or stiffness, especially after activity or when getting up from a seated position. There is still enough cartilage to prevent bones from rubbing together, but symptoms are starting to appear.

- Stage 3 (Moderate)

In the moderate stage, cartilage loss is more pronounced. Pain becomes more frequent and may interfere with daily activities such as walking, climbing stairs, squatting, or kneeling. Stiffness and reduced range of motion are common, and you may feel discomfort after periods of rest.

- Stage 4 (Severe)

Severe OA indicates that cartilage is nearly or completely gone in parts of the knee. Bones may grind together, causing constant pain, swelling, marked stiffness, and significant limitations in movement. At this point, conservative measures often provide limited relief, and joint replacement surgery may be discussed as an option.

What Causes Knee Osteoarthritis?

Knee osteoarthritis is caused by the gradual breakdown of cartilage in the knee joint.

While the exact cause of this breakdown is not always clear, several factors contribute to its development:

- Mechanical Stress: Research shows that overuse of the knee joint, especially among individuals who engage in repetitive activities or heavy lifting, can cause cartilage wear and tear.

- Inflammation: Chronic joint inflammation, often due to conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, can accelerate cartilage breakdown.

- Genetics: Modern research shows genetic factors can contribute to the development of knee osteoarthritis. If you have a family history of the condition, you may be more likely to develop it yourself.

- Joint Instability: Knee instability due to prior injuries or muscle strength imbalances can place additional stress on the joint, leading to cartilage damage.

- Obesity: Studies show that excess body weight puts additional pressure on the knee joint, leading to increased cartilage wear and tear.

What are the Symptoms of Knee Osteoarthritis?

The symptoms of knee osteoarthritis can vary depending on the severity of the condition.

Knee pain is the most common and noticeable symptom of knee osteoarthritis. You may feel discomfort when putting weight on your knee, during movement, or even while resting.

As the condition progresses, other symptoms can appear, including:

- Stiffness, especially when you first wake up or after sitting for long periods.

- Swelling or a puffy feeling around the knee joint.

- Cracking, popping, or grinding sounds (called crepitus) when you move the knee.

- A feeling of instability, as if the knee might buckle or “give out.”

- Locking or catching, where the knee briefly feels stuck or difficult to move.

These symptoms may come and go at first, but often become more frequent over time as osteoarthritis progresses.

Who is at Risk for Knee Osteoarthritis?

Several factors can increase the likelihood of developing knee osteoarthritis. Some of the key risk factors include:

- Age: As we age, the cartilage in our joints naturally wears down, increasing the risk of developing OA. It is most common in people over 50.

- Gender: Women are more likely than men to develop knee osteoarthritis, especially after menopause. This may be due to hormonal changes that affect the joints.

- Obesity: Excess body weight adds stress to the knee joint, increasing the risk of cartilage wear. Studies show that individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher are at significantly higher risk of developing knee OA.

- Previous Joint Injury: Individuals who have experienced a knee injury, such as a ligament tear or fracture, are at higher risk for developing OA later in life. Even if the injury heals, the knee joint may be weakened, leading to cartilage damage.

- Genetics: Some people may have a genetic predisposition to osteoarthritis. Certain genes may make individuals more susceptible to cartilage breakdown in the knee joint.

- Occupation: Jobs that require heavy lifting, kneeling, or squatting can increase the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis due to repetitive stress on the joint.

- Other Health Conditions: Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and diabetes can also increase the likelihood of developing knee osteoarthritis.

How is Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosed?

Knee osteoarthritis is typically diagnosed through a combination of physical examination, medical history, and imaging.

The following steps may be involved:

- Physical Examination: Your doctor will assess your knee’s range of motion, check for swelling or tenderness, and evaluate how well your knee functions during movement.

- Medical History: Your doctor will ask about your symptoms, any previous knee injuries, and your family history of osteoarthritis or other joint disorders.

- X-rays: X-rays are commonly used to evaluate the extent of joint damage and cartilage loss. They can show narrowing of the joint space, bone spurs, and other signs of OA.

- MRI: An MRI may be used if your doctor needs more detailed images of the soft tissues in your knee, including cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.

- Blood Tests: In some cases, blood tests may be done to rule out other conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, that may cause similar symptoms.

Knee Osteoarthritis Treatment Options

Knee osteoarthritis treatment focuses on relieving pain, improving mobility, and slowing the progression of joint damage.

Options range from lifestyle changes and nonsurgical therapies to surgical procedures. In most cases, healthcare providers begin with conservative (nonsurgical) treatments before considering surgery.

Nonsurgical treatments for knee OA

Nonsurgical options aim to reduce pain and inflammation, support joint function, and delay the need for surgery. Common treatments include:

- Pain Medications: Over-the-counter NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen) or acetaminophen can help reduce pain and swelling. Prescription options may be used if symptoms are more severe.

- Physical therapy: Targeted exercises strengthen the muscles around the knee, improve joint stability, and increase flexibility, making daily activities easier.

- Weight loss (when needed): Reducing body weight decreases stress on the knee joint. Even losing 5–10% of body weight can significantly reduce symptoms.

- Knee braces: Braces help support the joint, reduce strain, and may shift pressure away from the most damaged part of the knee.

- Corticosteroid (steroid) injections: These injections reduce inflammation and can provide short-term pain relief, especially during flare-ups.

- Knee gel injections (viscosupplementation): Hyaluronic acid “gel shots” add lubrication inside the joint to improve movement and reduce pain.

- Genicular nerve block injections: These target the small nerves around the knee to interrupt pain signals temporarily.

- Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections: PRP uses concentrated platelets from your own blood to promote healing and reduce joint inflammation.

- Genicular artery embolization (GAE): A minimally invasive procedure that reduces blood flow to inflamed tissues around the knee, helping decrease pain and swelling for some patients.

Surgical treatments for knee OA

Surgery is typically considered when pain is severe, daily function is limited, or nonsurgical treatments are no longer effective. Surgical options include:

- Cartilage restoration or replacement: Techniques such as microfracture, grafting, or implanting new cartilage aim to repair small areas of damage in younger, active patients.

- Knee bone reshaping (osteotomy): Surgeons cut and realign the bones around the knee to shift weight away from the damaged area, helping relieve pain and delay joint replacement.

- Partial knee replacement: Only the damaged portion of the knee is replaced with an artificial implant. This option preserves more of your natural knee and may lead to a faster recovery.

- Total knee replacement: The entire knee joint is replaced with artificial components. This is the most common surgical treatment for advanced knee OA and can provide long-lasting pain relief and improved mobility.

How Can Knee Osteoarthritis Be Prevented?

While you cannot entirely prevent knee osteoarthritis, there are several steps you can take to reduce your risk and protect your knee joint:

- Exercise Regularly: Engaging in low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, and walking can help strengthen the muscles around the knee and improve joint stability.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Reducing excess weight will reduce the pressure on your knees and help protect against OA.

- Avoid Joint Injuries: Protect your knees during physical activities, especially high-impact sports, by using proper techniques and wearing protective gear.

- Strengthen Your Muscles: Strengthening the muscles around the knee joint can help support the joint and reduce the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

- Stretch Regularly: Regular stretching can improve flexibility and reduce stiffness in the knee joint.

With these prevention strategies and staying proactive about your knee health, you can reduce your risk of developing knee osteoarthritis and maintain a high quality of life for years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does knee osteoarthritis feel like?

Knee osteoarthritis often feels like a combination of pain, stiffness, and joint grinding. You may notice aching pain during movement or after activity, stiffness when you first wake up or stand after sitting, and a cracking or grating sensation (crepitus) when the knee moves. Many people also experience knee swelling, a feeling that the knee is unstable or might “give out,” and occasional locking or catching when the joint gets stuck. As the condition progresses, you may find it harder to fully bend or straighten your knee, making everyday activities more difficult.

Leave a Reply