Urinary incontinence (UI) means leaking urine when you don’t want to. It is a common health problem that affects millions of people, especially women and older adults.

Over 33 million Americans suffer from some type of urinary incontinence or bladder condition.

Although it becomes more common with age, it is not a normal part of getting older. UI usually happens because the bladder cannot store urine properly, or the muscles that hold urine in become weak.

Importantly, it can affect daily life. People may feel embarrassed, avoid social activities, or feel stressed. For caregivers and family, UI increases physical and emotional strain.

But do you know what makes this problem even harder?

There is a lot of stigma around urinary incontinence, which makes people think leaking urine is “normal” after childbirth or as they get older. This stops many from asking for help.

In this blog, we’ll break down everything you need to know about urinary incontinence, its types, causes, symptoms, risks, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

With the right information, people can get help sooner, and healthcare providers can offer better care.

What is Urinary Incontinence?

Urinary incontinence (UI) means losing control of your bladder and accidentally leaking urine.

This can happen in different ways: you might leak a little when you cough or sneeze, feel a sudden urge to pee, or, in rare cases, lose full control of your bladder.

Your urinary system includes several organs that work together to filter, store, and remove waste as urine. When everything is working normally, you can get to the bathroom on time.

Incontinence happens when these organs or muscles don’t function properly. There are many reasons this can occur, and it can affect people at any stage of life.

While it’s true that the risk increases with age, UI can affect anyone, young or old.

The good news is that treatments are available to help manage it. With the right care, incontinence doesn’t have to disrupt your life or stop you from staying active.

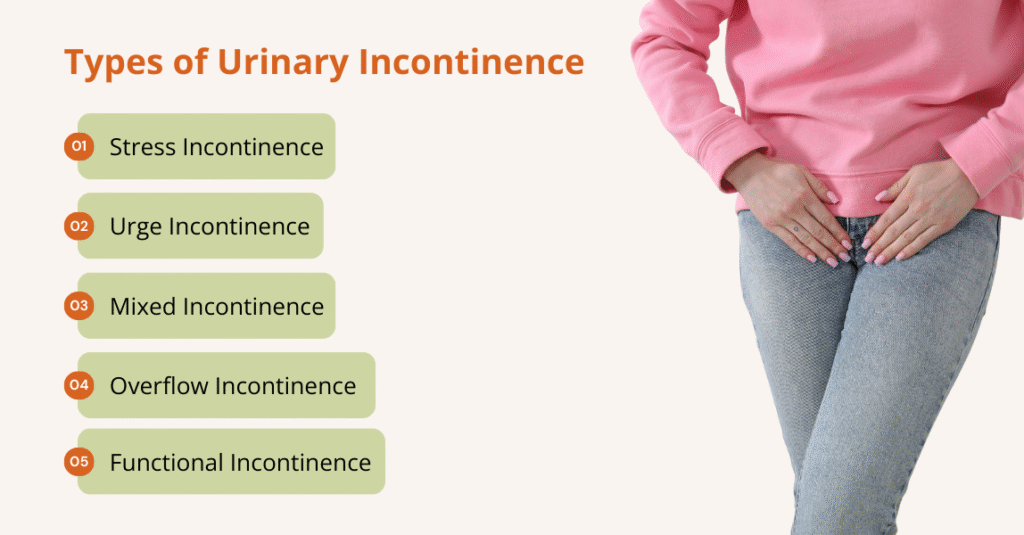

Types of Urinary Incontinence

There are several types of urinary incontinence, each with its own causes, symptoms, and triggers. Understanding which type you have is an important step in getting the right treatment.

The main types of incontinence include:

1. Stress Incontinence (SUI)

Stress incontinence (SUI) occurs when the pelvic floor muscles and/or urethral sphincter cannot resist sudden increases in intra‑abdominal pressure. Activities such as coughing, sneezing, laughing, exercising, or lifting heavy objects cause involuntary leakage.

In women, SUI commonly results from pregnancy, vaginal deliveries, and menopause, which weaken pelvic supports and the urethra. In men, it is frequently a postoperative complication of radical prostatectomy or transurethral resection of the prostate.

SUI is the most prevalent type in women; a cross‑sectional analysis of U.S. adults found that stress incontinence occurred in about 37.5% of women reporting incontinence.

2. Urge Incontinence (UUI)

Urge incontinence (UUI) is characterized by a sudden, intense urge to urinate followed by uncontrollable leakage. It is commonly associated with overactive bladder (OAB), a syndrome of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia.

Detrusor muscle overactivity is the principal mechanism; triggers include bladder inflammation or irritation (such as urinary tract infections), neurologic disorders (e.g., stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease), and aging.

According to NHANES data, UUI affects approximately 9–31% of U.S. women and 2.6–21% of men, with prevalence rising sharply after age 75.

3. Mixed Incontinence (MUI)

Mixed incontinence (MUI) combines both stress and urgency symptoms. Research shows that 20–30% of individuals with chronic incontinence have MUI.

People may experience leakage with physical activity and a sudden urge to void. It is common in older women and is associated with the same risk factors as SUI and UUI.

4. Overflow Incontinence (OFI)

Overflow incontinence results from chronic urinary retention; the bladder becomes overdistended and leaks constantly or intermittently.

Causes include obstruction of urine outflow (e.g., enlarged prostate, urethral stricture), neurologic diseases causing impaired detrusor contractility (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, spinal cord injury), or medications that affect bladder emptying.

Also, overflow incontinence is potentially dangerous because it can lead to urinary tract infections and, in severe cases, kidney damage.

5. Functional Incontinence (FUI)

Functional incontinence arises when a person cannot reach the toilet or remove clothing in time.

Causes are external to the urinary tract, mobility impairments, cognitive disorders such as dementia, visual impairment, or environmental barriers.

While often overlooked, functional incontinence significantly contributes to incontinence in frail older adults and nursing home residents.

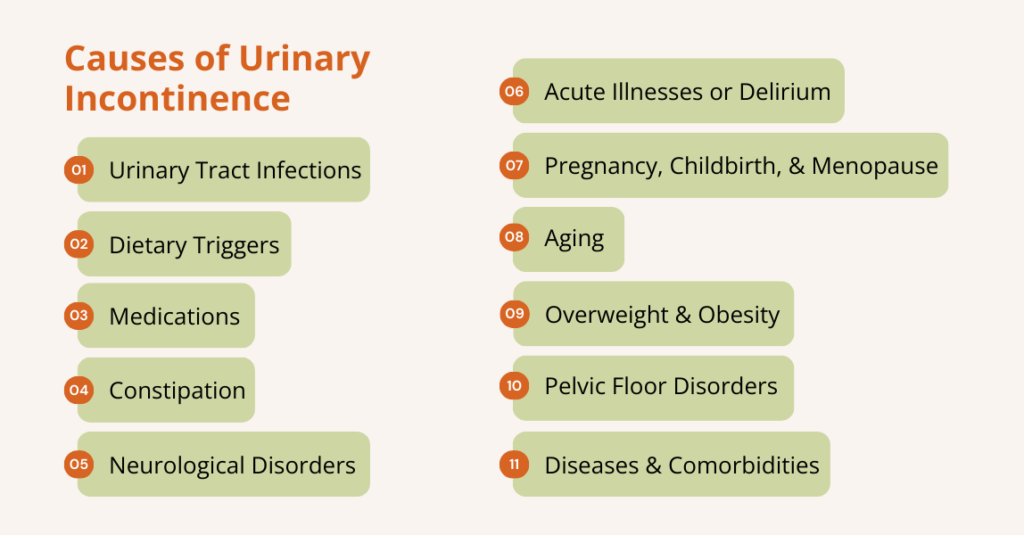

What Causes Urinary Incontinence?

Urinary Incontinence has multifactorial causes that can be temporary or persistent. Recognising the underlying cause is essential because treatment strategies vary.

Temporary Causes

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Infections can irritate the bladder, leading to sudden urges to urinate and leakage.

- Dietary Triggers: Foods and drinks like caffeine, alcohol, spicy foods, citrus fruits, carbonated drinks, and artificial sweeteners can irritate the bladder. Drinking large amounts of fluid or taking diuretics can also overwhelm the bladder.

- Medications: Diuretics increase urine production, while some sedatives, muscle relaxants, or anticholinesterase drugs can interfere with bladder or sphincter control.

- Constipation: Hard or impacted stool can put pressure on the bladder and block urine flow.

- Acute Illnesses or Delirium: Confusion from illness or delirium can make it harder to recognize the need to use the bathroom or get there in time.

Persistent or Long-Term Causes

Key persistent and long-term causes include:

- Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Menopause

Pregnancy and childbirth stretch and injure pelvic tissues and nerves. Vaginal delivery, instrument‑assisted birth, and having multiple births increase the risk of later SUI.

During menopause, declining estrogen causes atrophy of the urethral mucosa and pelvic connective tissue, reducing urethral closure pressure.

- Aging

Age‑related changes include reduced bladder capacity, diminished urethral sphincter tone, and decreased estrogen in women.

Detrusor muscle overactivity becomes more frequent with aging. Evidence from the CDC’s Rise for Health study shows that women with multiple chronic conditions had poorer bladder health than those with zero or one chronic condition.

- Overweight and Obesity

Excess body weight increases intra‑abdominal pressure and weakens pelvic floor muscles.

Another cross‑sectional study from NHANES 2013‑2018 reported that the weight‑adjusted waist index (WWI) was positively associated with urge urinary incontinence; each unit increase in WWI was associated with a 20% increase in UUI risk.

The study concluded that weight‑loss interventions could reduce UI in overweight women and clinically obese men.

- Neurological Disorders

Stroke, spinal cord injury, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), and diabetic neuropathy can disrupt neural control of the bladder and urethra.

For example, MS and spinal cord injury can cause detrusor overactivity or detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (outflow obstruction). Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias contribute to functional incontinence by impairing recognition of bladder signals or the ability to reach a toilet.

- Pelvic Floor Disorders and Connective Tissue Weakness

Pelvic organ prolapse, such as cystocele or rectocele, can displace the bladder and urethra. Loss of connective tissue strength (e.g., collagen disorders) predisposes to SUI. In men, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer can cause obstruction and overflow or stress UI.

- Diseases and Comorbidities

Diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease, asthma, and cardiovascular disease contribute to UI risk. Obesity‑related metabolic syndrome amplifies risk through systemic inflammation and hormonal changes.

A study using NHANES data found that sarcopenia was independently associated with increased risk of mixed and stress UI among women aged ≥60 and that sarcopenic obesity with a metabolically unhealthy phenotype conferred the highest risk.

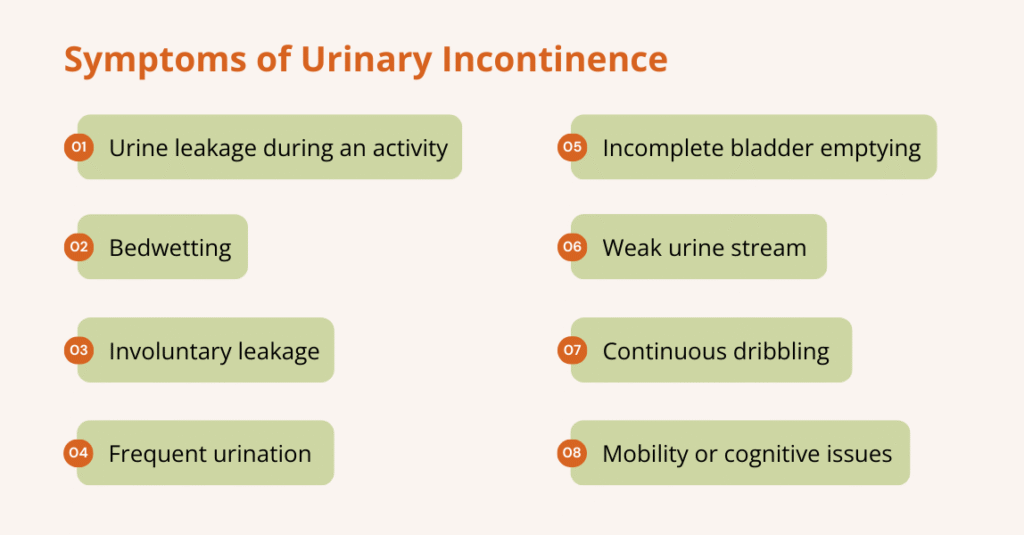

What are the Symptoms of Urinary Incontinence

The main symptom of urinary incontinence is leaking urine before reaching the bathroom or during activities. Leaks can be small or large, occasional or constant, and the exact symptoms often depend on the type of incontinence.

Common symptoms may include:

- Leaking urine during activities like coughing, sneezing, laughing, exercising, bending, or sexual activity

- Bedwetting (enuresis)

- Sudden, strong urge to urinate followed by involuntary leakage

- Frequent urination (more than 8 times a day), including waking at night (nocturia)

- Feeling that the bladder is full or unable to completely empty

- Weak urine stream or needing to strain to urinate

- Continuous dribbling or leakage without warning

- Difficulty reaching the toilet in time due to mobility or cognitive issues

Who Is More Likely to Develop Urinary Incontinence?

Women are roughly twice as likely as men to experience UI; hormonal changes, pregnancy, and childbirth account for much of this difference.

Moreover, age is a strong predictor; prevalence increases from 3.7% among people aged 65–69 to 10.6% among those aged ≥85.

Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status also influence risk; African American women have higher rates of urge or mixed UI, while white women are more likely to report stress UI.

Also, higher body‑mass index, diabetes, COPD, hypertension, and neurological disorders increase risk. Similarly, a study shows that sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and metabolic unhealthy obesity were shown to elevate the risk of stress and mixed UI markedly.

In addition, research also highlights that environmental exposures to endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (e.g., bisphenol A) may specifically raise the risk of urge UI.

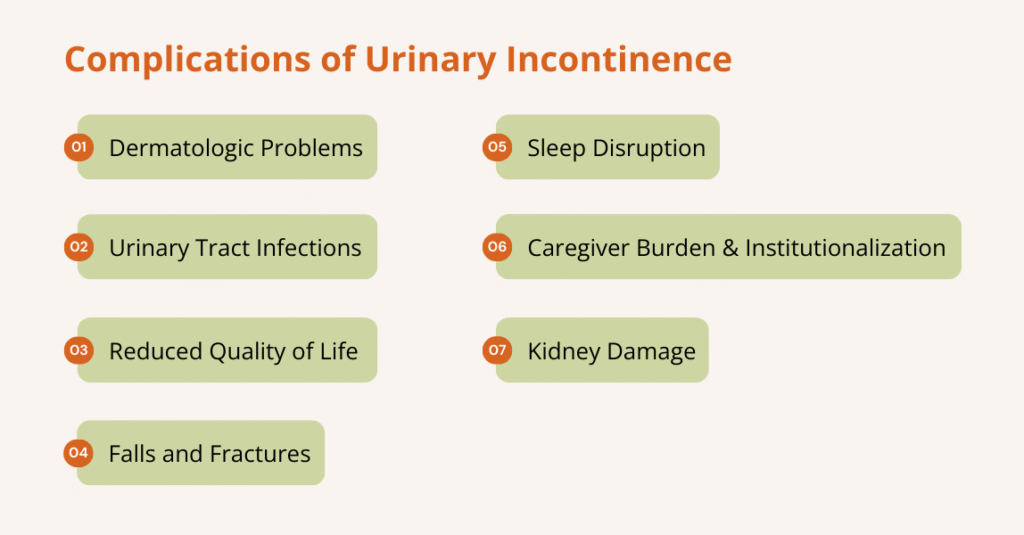

What are the Complications of Urinary Incontinence?

Chronic UI can lead to:

- Dermatologic Problems: Persistent wetness causes skin irritation, rashes, infections, and pressure ulcers.

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Incomplete emptying and catheter use increase the risk of UTIs.

- Reduced Quality of Life: People may restrict social interactions and physical activities to avoid accidents, leading to isolation, depression, and anxiety.

- Falls and Fractures: Rushing to the toilet increases the risk of falls, particularly among older adults.

- Sleep Disruption: Nocturnal urgency and voiding disturb sleep, causing fatigue and cognitive impairment.

- Caregiver Burden and Institutionalization: UI is a major reason for admission to long‑term care, and study shows that more than 50% of nursing home residents and 75% of long‑term care residents have UI.

- Kidney Damage: Chronic urinary retention in overflow incontinence can lead to hydronephrosis and renal failure.

How Is Urinary Incontinence Diagnosed?

A thorough evaluation is essential to determine the type and cause of UI. Here’s how:

- History & Physical Examination

The Doctor asks about when and how often leaks happen, fluid intake, medications, and health history. They check your abdomen/pelvis and may do a “cough stress test” to see if leakage happens with pressure.

- Bladder Diary

You record when you drink, when you pee, how much, and when leaks occur (for several days). This helps identify patterns and triggers.

- Urinalysis & (if needed) Urine Culture

A urinalysis checks for urinary tract infection (UTI), blood, sugar, or other abnormalities that might explain incontinence. Also, blood tests are sometimes performed to evaluate kidney function or detect other systemic conditions. These blood tests assess renal function, glucose, calcium, and electrolytes.

- Post-Void Residual Measurement

After you urinate, a test (via ultrasound or catheter) may measure how much urine remains in your bladder. If a large amount remains, this may indicate incomplete bladder emptying (overflow or neurogenic bladder).

- Bladder Function (Urodynamic) Tests

For more complex or unclear cases, tests such as uroflowmetry, cystometry, or pressure-flow studies assess how well your bladder and sphincter store and release urine.

- Cystoscopy or Imaging

If there’s suspicion, endoscopic or radiographic evaluation is performed to assess for abnormalities, bladder stones, tumors, or fistulas.

Urinary Incontinence Treatment Options

Treatment should be individualized based on the type of incontinence, severity, age, sex, and comorbidities.

Management usually follows a stepwise approach: lifestyle modifications, behavioral therapies, medications, devices, and surgery.

Lifestyle Changes

These are first‑line strategies recommended for all patients because they have minimal side effects and address reversible factors.

A frontiers study of 20,195 adults found that adherence to 4–5 healthy lifestyle factors (non‑smoking, moderate alcohol intake, regular physical activity, healthy diet, and optimal waist circumference) reduced the risk of overactive bladder by 46% compared with adherence to 0–1 factors.

Here are some lifestyle and behavioral therapies to consider:

- Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT)

Also called Kegel exercises, PFMT strengthens the levator ani and urethral sphincter. People contract and relax pelvic muscles in sets of 10–15 squeezes, three times daily.

Evidence indicates that PFMT improves or resolves symptoms in two-thirds of women. Men benefit as well; PFMT is recommended after prostate surgery.

- Lifestyle Modifications

Maintain a healthy weight, treat chronic cough, manage diabetes and constipation, stop smoking, reduce alcohol and caffeine intake, and avoid bladder irritants.

- Fluid Management

Drink adequate fluids (about 6–8 glasses daily) and avoid excessive intake. Avoid drinking right before bedtime.

Behavioral Therapies

Behavioral therapies help retrain the brain–bladder connection and reduce anxiety, urgency, and leakage through mental and emotional techniques.

- Bladder Training and Timed Voiding

For urgency or mixed incontinence, patients gradually increase intervals between voids and use urge‑suppression techniques. This helps expand bladder capacity and reduce urgency.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT helps individuals modify thoughts and behaviors that exacerbate urgency or fear of leaking. It teaches coping strategies, reduces bathroom-related anxiety, and improves confidence in bladder control.

Physical Therapies

Physical therapy focuses on strengthening and retraining the pelvic floor muscles to improve bladder control and reduce leakage.

- Pelvic Floor Muscle Rehabilitation

This involves learning to strengthen and control the pelvic floor muscles, as they support the bladder and help prevent urinary leakage.

A physical therapist teaches proper techniques (similar to Kegel exercises). Therapy may also include breathing techniques and core strengthening to improve overall pelvic stability.

- Biofeedback and Electrical Stimulation

Biofeedback uses sensors to display muscle activity on a screen, helping you learn when you’re contracting the right muscles and how to improve control.

Whereas electrical stimulation delivers a gentle current to activate weak pelvic floor muscles, strengthen them over time, and reduce symptoms like urgency, frequency, and leakage.

Together, they help improve muscle awareness, coordination, and bladder control.

Medications

Medication is usually considered when behavioral therapies don’t provide enough relief.

Common drug options include:

- Anticholinergics (Antimuscarinics)

Antimuscarinic agents (e.g., oxybutynin, tolterodine, solifenacin) are used to relax the bladder muscle to reduce urgency, frequency, and urge-related leakage.

In U.S. Medicare data, antimuscarinics remain the most commonly prescribed, but their use decreased from 49% to 34% between 2012 and 2021, while β‑3 agonist use increased from 0.2% to 17%.

- Beta-3 Agonists

These drugs (e.g., mirabegron, vibegron) also relax the bladder muscle but typically have fewer cognitive side effects than anticholinergics.

- Topical Estrogen

Low-dose vaginal estrogen can improve urethral and vaginal tissue health, reduce irritation, and improve stress or urgency symptoms in postmenopausal women.

It is not the same as systemic hormone therapy and has minimal systemic absorption.

- Medications for Men with BPH-Related Incontinence

For men with bladder symptoms caused by prostate enlargement, alpha-blockers (e.g., tamsulosin, terazosin) help relax the prostate and bladder neck. Whereas 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (e.g., finasteride, dutasteride) shrink the prostate over time. Often, these medications are combined for better symptom control.

Minimally Invasive Procedures

These treatments are considered when lifestyle changes and medications aren’t enough and offer effective, low-risk options to improve bladder control.

- Botox Injections for Overactive Bladder

Botox is injected into the bladder muscle to calm overactive contractions. This reduces urgency, frequency, and the risk of sudden leakage. Results typically last 6–12 months.

- Sacral Neuromodulation (Nerve Stimulation Therapy)

A small device sends gentle electrical pulses to the sacral nerves, which control bladder function. This helps restore normal signaling and reduces urge incontinence and urinary retention.

- Urethral Bulking Agents

A gel-like material is injected around the urethra to facilitate closure. This provides extra support and reduces stress incontinence, especially in women with weak sphincter muscles.

Surgical Treatments

These procedures are considered when other treatments fail or when incontinence is severe and linked to structural problems.

- Mid‑urethral Sling Procedures

A mesh or tissue sling is placed under the urethra to provide support. It helps maintain urethral closure during coughing, laughing, or exercise, making it highly effective for stress urinary incontinence in women.

- Artificial Urinary Sphincter (AUS) Implantation

AUS is most commonly used in men, especially after prostate surgery. It involves placing an inflatable cuff around the urethra, which opens and closes via a small pump. This provides strong control for moderate to severe incontinence.

- Bladder Neck Suspension

This surgery lifts and secures the bladder neck and urethra into a better position. It helps reduce leakage caused by weak support tissues and is often used for stress incontinence in women.

- Cystoplasty (Bladder Augmentation)

This procedure enlarges the bladder using a piece of bowel. It increases bladder capacity and reduces pressure, making it useful for severe urge incontinence or neurogenic bladder when other treatments have failed.

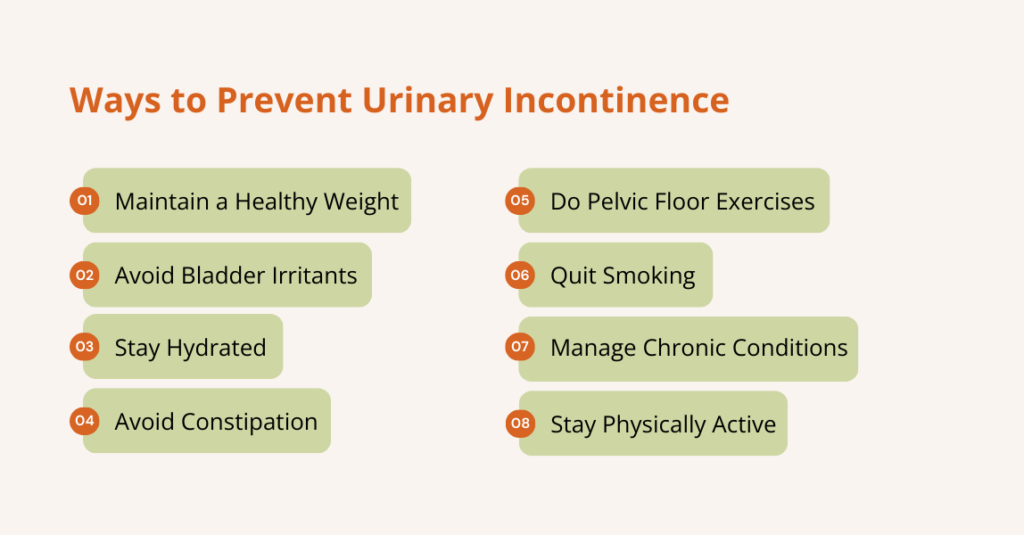

How to Prevent Urinary Incontinence?

You can lower your risk of urinary incontinence by protecting your pelvic floor and managing lifestyle factors: Here’s how:

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Keeping your BMI in a healthy range reduces pressure on your bladder. Weight-loss programs are especially effective for overweight women and obese men.

- Avoid Bladder Irritants: Cut back on caffeine, alcohol, carbonated drinks, artificial sweeteners, spicy foods, and citrus. Some people also react to chocolate and acidic foods.

- Stay Hydrated: Drink enough water to keep urine light-colored, but don’t overdrink. Dehydration can irritate the bladder and increase the risk of UTIs.

- Prevent Constipation: Eat more fiber, drink plenty of fluids, and stay active. Constipation can worsen bladder leakage.

- Do Pelvic Floor Exercises: Practice PFMT regularly, including during and after pregnancy, to keep pelvic muscles strong.

- Quit Smoking: Smoking causes chronic coughing, which strains pelvic muscles and increases SUI risk.

- Manage Chronic Conditions: Keep conditions like diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and COPD under control to protect bladder function.

- Stay Physically Active: Regular exercise supports weight control and muscle strength. Avoid too many high-impact activities if they trigger leakage; balance them with PFMT.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can urinary incontinence be cured?

Many people achieve significant symptom improvement or complete resolution, especially with early intervention. Lifestyle and behavioral therapies (PFMT, bladder training) are effective first‑line treatments. For persistent symptoms, medications, neuromodulation, or surgery can provide relief. Cure rates vary by type and severity; for example, research shows that PFMT cures or improves symptoms in roughly 67% of women, while mid‑urethral sling surgery for SUI has long‑term success rates around 80%. Urge incontinence often requires combination therapy; Botox and sacral neuromodulation have similar efficacy at two years.

Is urinary incontinence a normal part of aging?

No. Although prevalence increases with age, UI is a medical condition, not an inevitable consequence of aging. Many older adults maintain continence with proper bladder health habits, pelvic floor exercises, and management of chronic diseases.

Will drinking less water help with incontinence?

Restricting fluid intake can worsen urinary symptoms because concentrated urine irritates the bladder. Instead, spread fluid intake throughout the day and limit fluids before bedtime. Avoid caffeinated or carbonated beverages, as they can’t stimulate the bladder.

When should I see a healthcare provider about incontinence?

You should consult a clinician if you experience involuntary leakage that affects daily life; have associated symptoms such as burning, pain, blood in urine, or frequent UTIs; or have difficulty emptying your bladder. Early evaluation helps identify reversible causes and prevents complications.

Conclusion

For many people, talking about bathroom habits can feel embarrassing. However, it is a common and often overlooked condition that affects millions of Americans.

Urinary incontinence may make you self-conscious or keep you from enjoying daily activities because you’re worried about leaking or not reaching the bathroom in time.

Therefore, promoting bladder health, encouraging early symptom reporting, and supporting lifestyle changes are essential.

Most individuals can achieve meaningful improvement through weight management, pelvic floor exercises, bladder training, and appropriate medications or procedures.

If you’re experiencing any signs of incontinence, don’t wait; taking action now can help you prevent discomfort and bigger problems later in life.

Leave a Reply