Uterine fibroids (also called leiomyomas) are benign tumours made of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue that form in or on the muscular wall of the uterus.

It can range in size from a seedling to masses bigger than a melon.

Epidemiological analyses estimate that 40–80 % of people with a uterus have fibroids, with the greatest prevalence between 30 to 50 years.

Despite being non‑malignant, fibroids can severely affect quality of life by causing heavy menstrual bleeding, chronic pelvic pain, pressure symptoms, infertility, or pregnancy complications.

Moreover, new survey data from The Harris Poll for the Society of Interventional Radiology show that many women still have misunderstandings about their treatment options.

In fact, 17% believe a hysterectomy, the complete removal of the uterus, is the only solution, including 27% of women aged 18–34. However, minimally invasive treatments like UFE, in addition to surgical treatment, are a great option.

This article explains uterine fibroids, including their types, causes, symptoms, complications, and treatment options.

What are Uterine Fibroids?

Uterine fibroids are non-cancerous (benign) growths that develop in the wall of the uterus. They are made of smooth muscle cells and fibrous (connective) tissue. Fibroids can be as small as a pea or as large as a grapefruit, and a woman may have one fibroid or many.

Most fibroids grow slowly or not at all and do not turn into cancer. Fibroids are usually described by where they grow:

- Submucosal

- Intramural

- Subserosal

Each fibroid’s size and location influence the symptoms a person may have and which treatments are appropriate.

Who Usually Develops Uterine Fibroids?

Fibroids are most common in women of reproductive age, particularly between about 30 and 50 years old. The risk increases with age during the childbearing years and then generally decreases after menopause.

Evidence from epidemiological and mechanistic research identifies several modifiable and non‑modifiable risk factors:

| Risk Factor | Evidences |

| Race/ethnicity | Research shows that black women are about three times more likely to develop fibroids than the general population, often experiencing earlier onset, larger fibroids, and more severe symptoms such as pelvic pain, menopause, bladder problems, and heavy bleeding. |

| Genetic predisposition | Having close relatives with fibroids increases the risk, with genetic predisposition playing a significant role. |

| Age, early menarche & late menopause | Fibroids are rare before puberty; incidence peaks in the 40s and declines after menopause. Early menarche and late menopause prolong estrogen exposure and increase risk. |

| Obesity and high BMI | A nutritional review shows that obesity increases aromatase activity, converting androgens to estrogens, which stimulate fibroid growth. |

| Hypertension | A longitudinal analysis of 2,570 midlife women found that untreated hypertension was associated with a 19 % higher risk of incident fibroids, whereas antihypertensive medication reduced risk by 37 %. Participants who developed hypertension during follow‑up had a 45 % increased risk. |

| Nulliparity | Women who have not delivered children have a higher risk. Pregnancy may be protective because uterine remodelling during pregnancy may reduce the number of uterine stem cells. |

| Hormonal factors | A study highlights that prolonged exposure to estrogen and progesterone stimulates growth; fibroids enlarge during pregnancy and shrink after menopause. |

| Vitamin D deficiency | Low vitamin D levels increase risk; supplementation may inhibit fibroid growth. |

| Environmental factors | Research indicates diets high in red meat, saturated fats, and alcohol, exposure to endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (e.g., organophosphate esters, plasticizers), tobacco use, and vitamin D deficiency have been associated with increased risk. |

| Genitourinary microbiome & inflammation | Alterations in the reproductive tract microbiome and chronic low‑grade inflammation may promote fibroid growth. |

3 Types of Uterine Fibroids

Fibroids are classified according to their location in the uterus and relationship to the uterine wall.

The most commonly used system is the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification. For clinical purposes, three broad types are usually discussed:

1. Submucosal Fibroids

Grow just beneath the uterine lining and can protrude into the uterine cavity. They’re the type most likely to cause heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding and fertility problems because they distort the lining where an embryo would implant.

2. Intramural Fibroids

Form inside the muscular wall of the uterus and are the most common type. They can make the uterus feel larger, cause pelvic pain or pressure, and may contribute to heavy bleeding and fertility issues, depending on size and exact location.

3. Subserosal Fibroids

Develop on the outer surface of the uterus and grow outward. These usually cause bulk-related symptoms, such as pelvic pressure, pain, or urinary/bowel problems, from pressing on nearby organs. Some subserosal fibroids are pedunculated (stalked) and can cause acute pain if they twist.

Clinical Note: The fibroid’s location strongly affects symptoms and treatment choices. For example, submucosal fibroids are often removed hysteroscopically to improve bleeding or fertility, while large intramural or subserosal fibroids may need other surgical or radiologic approaches.

What Causes Uterine Fibroids?

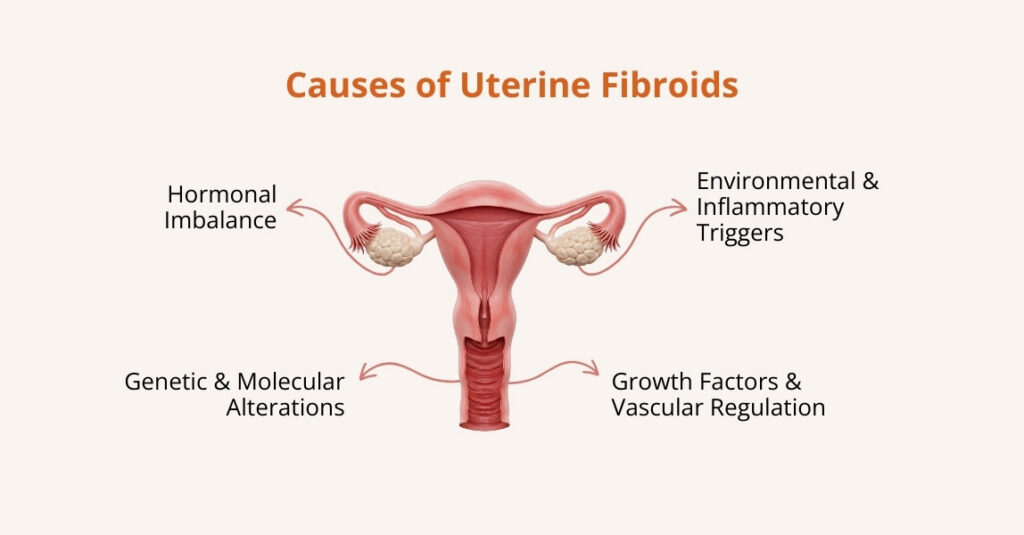

The exact cause of fibroid development is still unclear, but several mechanisms are implicated:

- Hormonal Imbalance

Estrogen and progesterone promote the proliferation of smooth muscle cells and the extracellular matrix in fibroids. Fibroids contain more estrogen and progesterone receptors than normal myometrium.

Hormone fluctuations explain why fibroids grow during pregnancy and shrink after menopause.

- Genetic and Molecular Alterations

Somatic mutations in the MED12 gene are the most common driver mutation, detected in 45–90% of fibroids. Other genes can also be involved. These changes make the cells grow more than they should.

- Growth Factors and Vascular Regulation

Fibroids produce growth factors (e.g., transforming growth factor‑β and vascular endothelial growth factor) and exhibit altered angiogenic signalling, leading to increased vascularisation and fibroid growth.

- Environmental and Inflammatory Triggers

Vitamin D deficiency, endocrine‑disrupting chemicals, chronic inflammation, and obesity contribute to pathogenesis by altering hormone metabolism and extracellular matrix deposition.

What are the Symptoms of Uterine Fibroids?

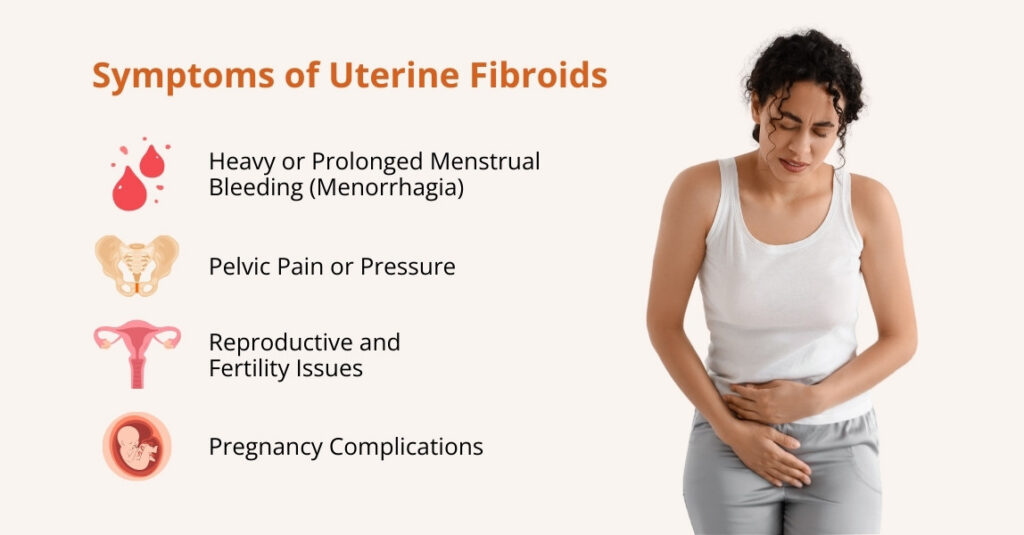

Symptoms depend on the size, number, and location of fibroids; many women are asymptomatic.

The most common symptoms include:

- Heavy or Prolonged Menstrual Bleeding (Menorrhagia)

Submucosal fibroids, which grow close to the uterine lining, are the most likely to cause heavy, long, or irregular periods. This type of bleeding can be severe enough to lead to iron-deficiency anemia, causing fatigue, weakness, or shortness of breath.

- Pelvic Pain or Pressure

Larger intramural or subserosal fibroids can press on nearby organs. This pressure may cause:

- Low back pain

- A swollen or enlarged abdomen

- Urinary frequency or difficulty emptying the bladder

- Constipation or discomfort during bowel movements

These symptoms are caused by the fibroid pushing against the bladder, bowel, or pelvic nerves.

- Reproductive and Fertility Issues

Fibroids can affect fertility by changing the shape of the uterus, blocking the fallopian tubes, or interfering with embryo implantation. They may also increase the risk of miscarriage.

Studies show fibroids are found more in women seeking fertility treatment, and both the number and size of fibroids are directly linked to how severe symptoms are and how much they impact quality of life.

- Pregnancy Complications

During pregnancy, fibroids can increase the risk of:

- Difficulty becoming pregnant

- Preterm birth

- Breech presentation

- Heavy bleeding after delivery (postpartum hemorrhage)

The risk depends heavily on the fibroid’s location and size. Some fibroids remain stable during pregnancy, while others may grow due to higher hormone levels.

What are the Risk Factors for Uterine Fibroids?

Several factors can increase a woman’s chances of developing uterine fibroids:

- Family history: Women with a mother or sister who had fibroids are more likely to develop them.

- Age (30–50 years): Fibroids usually appear and grow during the reproductive years, especially in the 30s and 40s, then often shrink after menopause.

- Obesity and high blood pressure: Higher body weight and hypertension are both linked to a greater risk of fibroids.

- Lifestyle factors: Low physical activity, a diet high in red meat, and low intake of fruits and vegetables may contribute to fibroid growth.

- Early menstruation and late menopause: Starting periods at a young age and going through menopause later in life expose the uterus to hormones for longer, increasing the chance of developing fibroids.

What are the Complications of Uterine Fibroids?

Besides the symptoms listed above, fibroids can lead to specific complications:

- Anemia from Heavy Bleeding

When fibroids, especially those near the uterine lining, cause heavy or prolonged periods, chronic blood loss can lead to iron-deficiency anemia. This may require iron supplements or other medical treatment to restore iron levels.

- Infertility and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

A study shows that large submucosal fibroids (those that grow into the uterine cavity) are linked with infertility and a higher risk of miscarriage and preterm birth.

For selected patients, removing submucosal fibroids with hysteroscopic myomectomy has been shown to improve reproductive outcomes. However, the benefit depends on the fibroid type and individual factors.

- Urinary and Bowel Dysfunction

Fibroids that press on the bladder or rectum can cause urinary frequency, urgency, difficulty emptying the bladder, or constipation and discomfort during bowel movements.

These “bulk” effects come from the fibroid’s size and location rather than bleeding.

- Rare Risk of Cancer

Malignant transformation of a fibroid into a leiomyosarcoma is extremely rare (well under 1% of cases). Because the risk is small but clinically important, doctors evaluate rapidly growing or suspicious masses carefully.

How are Uterine Fibroids Diagnosed?

Evaluation begins with a clinical history and pelvic examination. The choice of test depends on symptoms, suspected fibroid location, and whether fertility is a concern.

Initial Assessment

- Pelvic Exam: A doctor may feel an enlarged or irregular uterus during a routine pelvic exam, which can suggest the presence of fibroids.

- Medical History and Symptoms: Information about heavy bleeding, pelvic pain, or urinary problems helps guide which tests are needed.

Imaging Tests

- Pelvic Ultrasound (first-line test): Ultrasound is the most common and readily accessible modality for detecting fibroids. It shows their size, number, and basic location.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI provides detailed fibroid mapping and is useful for surgical planning or when ultrasound results are inconclusive.

- CT Scan: CT is not routinely used to diagnose fibroids, but it may show them incidentally if performed for another reason.

Procedures for Uterine Cavity Assessment

- Hysteroscopy or Hysterosalpingography: Hysteroscopy allows direct visualisation and treatment of submucosal fibroids. Hysterosalpingography helps evaluate intracavitary lesions.

- Laparoscopy: Used when other imaging is inconclusive or when concomitant pelvic pathology is suspected.

Additional Tests

- Blood Tests: These help check for anemia from heavy bleeding and rule out other causes of symptoms.

Uterine Fibroids Treatment Options

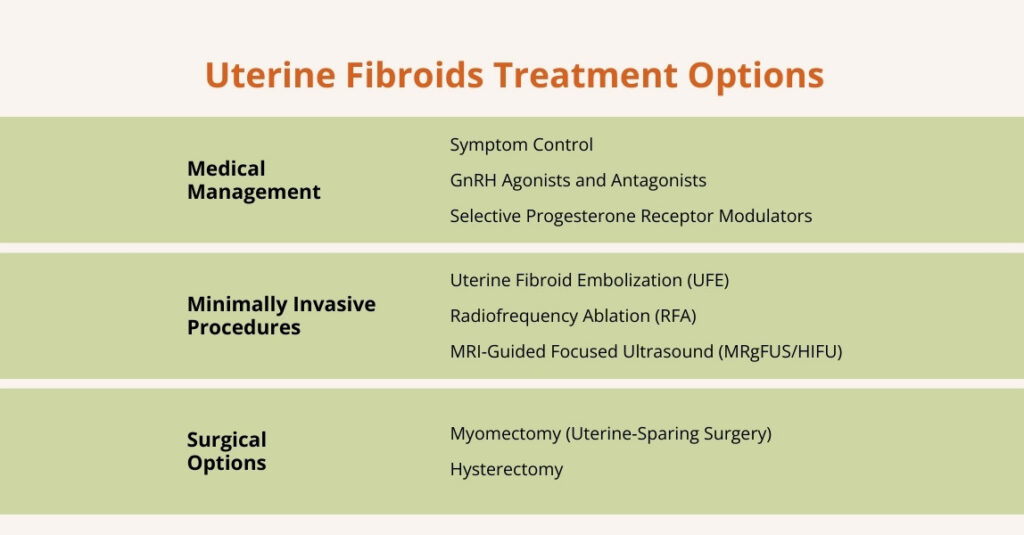

Uterine treatment decisions depend on fibroid size, location, symptom severity, patient age, and fertility desires. Many small or asymptomatic fibroids can be monitored (“watchful waiting”).

Symptomatic fibroids may require medical therapy, minimally invasive procedures, or surgery.

Here are some options supported by recent evidence and guideline recommendations.

Medical Management

- Symptom Control

Symptom control is the goal of medical therapy; medications generally do not eradicate fibroids but can reduce bleeding and shrink tumours.

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, first‑line agents include oral contraceptive pills and progestin‑containing intrauterine devices, which reduce bleeding symptoms.

Non‑hormonal alternatives such as tranexamic acid are effective for heavy menstrual bleeding.

- GnRH Agonists and Antagonists

Two types of medicines can shrink fibroids and reduce symptoms: GnRH agonists (such as leuprolide) and GnRH antagonists (such as elagolix, linzagolix, and relugolix).

Research shows that these medicines work by lowering estrogen levels, which in turn causes fibroids to shrink. Because low estrogen can cause side effects such as hot flashes and bone thinning, they are usually used for a short time, often to shrink fibroids before surgery.

Newer treatments combine a low dose of estrogen and progestin with the medication. This helps prevent strong side effects while still controlling heavy menstrual bleeding, and this approach is FDA-approved.

- Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulators (SPRMs)

Drugs such as ulipristal acetate reduce bleeding and fibroid size, but concerns about hepatotoxicity have limited widespread use.

Other Agents: NSAIDs relieve pain; combined oral contraceptives, progestin injections or implants, and the levonorgestrel intrauterine device control bleeding. Iron supplementation addresses anemia.

Minimally Invasive Procedures

- Uterine Fibroid Embolization (UFE)

Uterine fibroid embolization is a catheter‑based procedure performed by Dr. Zagum Bhatti, a board-certified interventional radiologist..

A catheter is introduced through the femoral or radial artery and navigated into the uterine arteries; small embolic particles occlude the branches supplying the fibroids, causing ischemic necrosis and shrinkage.

Randomised trials show that UFE provides symptom relief comparable to myomectomy; quality‑of‑life scores and re‑intervention rates at four years are not significantly different. Advantages include a shorter hospital stay, lower risk of blood transfusion, and faster recovery.

However, patients may experience post‑embolization syndrome (pelvic pain, fever, nausea) and expulsion of submucosal fibroids.

Another retrospective study of 155 patients undergoing UFE for submucosal fibroids found that UFE reduced the median volume of the dominant fibroid by 64% and achieved >90% devascularization in 94.8% of cases.

High patient satisfaction was reported, with 84.5% discharged without further intervention.

Severe adverse events were rare (3.2 %), while mild adverse events (mainly infection or vaginal discharge) occurred in 16.8 %. These findings support UFE as an effective and safe option for submucosal fibroids.

- Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

RFA (available as laparoscopic Acessa or transcervical Sonata systems) uses thermal energy to coagulate fibroid tissue.

Under ultrasound guidance, a needle electrode delivers radiofrequency energy, heating the fibroid to ~100 °C and causing coagulative necrosis, which is gradually reabsorbed. RFA is typically a day surgery and preserves the uterine wall structure.

- MRI‑Guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS/HIFU)

MRgFUS uses high‑intensity focused ultrasound waves to thermally ablate fibroid tissue under MRI guidance. Advantages include no incisions, minimal blood loss, and rapid recovery.

According to the ACR Appropriateness Criteria, complications are rare but can include skin burns, nerve injury, and deep vein thrombosis.

Compared with UFE, MRgFUS has longer procedure times and higher re‑intervention rates.

Surgical Options

- Myomectomy (Uterine‑Sparing Surgery)

Myomectomy removes fibroids while preserving the uterus and fertility. It can be performed hysteroscopically (for submucosal fibroids), laparoscopically/robotically, or via open abdominal surgery.

- Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) provides definitive treatment with no risk of recurrence, making it appropriate for women who do not desire future fertility.

Options include total hysterectomy (uterus and cervix removed), supracervical hysterectomy (uterus only), and may be performed vaginally, laparoscopically, or abdominally.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Are Uterine fibroids common?

Yes. About 40–80% of people with a uterus develop fibroids, with the highest prevalence between ages 30 and 50. Most fibroids are small and cause no symptoms, so many people only find out about them during a pelvic exam or ultrasound.

Do uterine fibroids cause pain?

Many women experience pelvic pressure or pain; symptoms depend on fibroid size and location. Submucosal fibroids often cause heavy bleeding, while large intramural or subserosal fibroids can cause back pain, urinary frequency, and constipation.

Can uterine fibroids be cancerous?

Fibroids are almost always benign. Malignant transformation into leiomyosarcoma (cancer) is extremely rare.

What size of uterine fibroids should be removed?

There is no single size threshold. Indications include significant symptoms (heavy bleeding, pain, infertility), rapid growth, or distortion of the uterine cavity. Fibroids larger than 5 cm or submucosal fibroids causing heavy bleeding often warrant intervention.

Can uterine fibroids cause bleeding?

Yes. Heavy menstrual bleeding is one of the most common symptoms and can lead to iron‑deficiency anemia. Iron supplementation or treatment to reduce bleeding may be necessary.

Can uterine fibroids cause anemia?

Yes, uterine fibroids can lead to anemia. This happens when heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding caused by fibroids depletes the body’s iron stores, which are essential for making red blood cells. Over time, this can lead to a low red blood cell count, resulting in fatigue, weakness, and other anemia-related symptoms.

Can I get pregnant with uterine fibroids?

Yes, you can get pregnant with a uterine fibroid, but it can sometimes affect fertility or pregnancy depending on its size, number, and location. Submucosal fibroids, which grow into the uterine cavity, are most likely to interfere with embryo implantation or increase the risk of miscarriage. Large intramural fibroids within the uterine wall can also reduce fertility or cause complications, while subserosal fibroids on the outer surface usually do not affect fertility but may cause discomfort if very large. Doctors may recommend monitoring, medication, or surgical removal for fibroids that could interfere with conception or a healthy pregnancy.

Do uterine fibroids go away on their own?

Uterine fibroids usually do not disappear on their own, but their growth often slows or stops after menopause when hormone levels (estrogen and progesterone) decline. Some small fibroids may remain stable for years without causing symptoms, so not all fibroids require treatment. Doctors often monitor fibroids that aren’t causing problems and only recommend intervention if they grow, cause symptoms, or affect fertility.

Can uterine fibroids be prevented?

No, uterine fibroids cannot always be prevented. However, certain lifestyle choices may help reduce the risk or slow their growth. Maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, eating a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and fiber, controlling blood pressure, getting enough vitamin D, limiting alcohol and red meat, and using certain hormonal contraceptives may all help. While these steps don’t guarantee prevention, they can support overall uterine health and may reduce the chances of fibroids developing or growing quickly.

Leave a Reply